Anthropomorphism is a term I hear a lot around biologists. It describes a thing we all do, attributing human characteristics to non-human things. Whether giving voices to our favorite stuffed animals as children to dressing our pets in clothing (disclaimer, our dog is snoring at my feet as I write this in an adorable Christmas sweater), we can’t seem to resist applying the human experience to everything around us. That’s not to say it’s a bad thing, our pooch likes the extra warmth and her sweater is straight up adorbs, but in the world of environmental conservation, it can work for and against you.

Anthropomorphism is a term I hear a lot around biologists. It describes a thing we all do, attributing human characteristics to non-human things. Whether giving voices to our favorite stuffed animals as children to dressing our pets in clothing (disclaimer, our dog is snoring at my feet as I write this in an adorable Christmas sweater), we can’t seem to resist applying the human experience to everything around us. That’s not to say it’s a bad thing, our pooch likes the extra warmth and her sweater is straight up adorbs, but in the world of environmental conservation, it can work for and against you.

A local fisherman heads to shore on Lake Aleknagik in Southwestern Alaska.

One inevitable side effect of anthropomorphizing animals is that it can create heaps of unconscious bias. Sharks, for example, are often perceived as evil and menacing while dolphins are loving and approachable, even though sharks are often timid and docile while cetaceans can be violent and aggressive. If a species is charismatic and somehow relatable, people are more likely to form attachments and “love” them. And as Baba Dioum famously put it, “we will conserve only what we love”.

One inevitable side effect of anthropomorphizing animals is that it can create heaps of unconscious bias. Sharks, for example, are often perceived as evil and menacing while dolphins are loving and approachable, even though sharks are often timid and docile while cetaceans can be violent and aggressive. If a species is charismatic and somehow relatable, people are more likely to form attachments and “love” them. And as Baba Dioum famously put it, “we will conserve only what we love”.

This past summer, on a plane headed north to Alaska, I spent a lot of time thinking about how to get people to care about a type of animal that often feels totally alien to us terrestrial critters: fish. We were working on our new line of advocate apparel and this trip would be our introduction to the species, sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). For sure many people “love” fish, especially salmon, but that love often feels commodified in the same way we might love chocolate or a bouquet of flowers. Spend time with a cow mothering her calf or a goofy piglet and I suspect most people will feel a stronger connection with their next steak or ham sandwich. But when it comes to fish, I think we struggle to form an interspecies bond.

This past summer, on a plane headed north to Alaska, I spent a lot of time thinking about how to get people to care about a type of animal that often feels totally alien to us terrestrial critters: fish. We were working on our new line of advocate apparel and this trip would be our introduction to the species, sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). For sure many people “love” fish, especially salmon, but that love often feels commodified in the same way we might love chocolate or a bouquet of flowers. Spend time with a cow mothering her calf or a goofy piglet and I suspect most people will feel a stronger connection with their next steak or ham sandwich. But when it comes to fish, I think we struggle to form an interspecies bond.

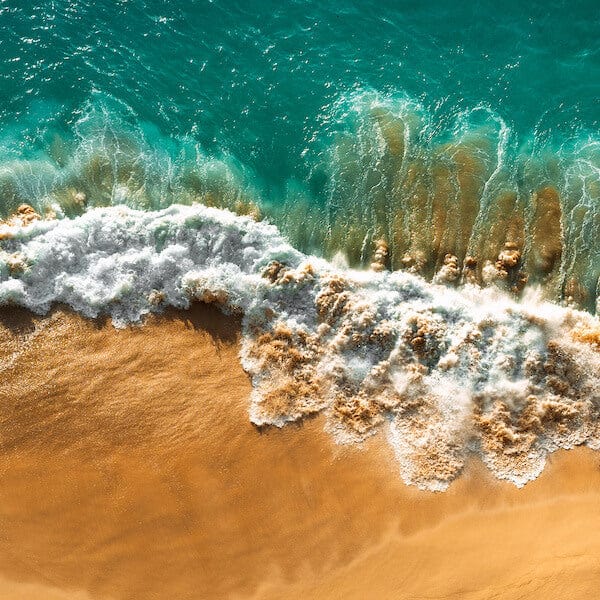

The University of Washington built their first field station on Lake Aleknagik in 1947. Much of the original infrastructure here has been modernized, but the stunning view has stayed the same.

Nemo aside, fish are often cast as brainless, slimy and smelly characters in Earth’s ecosystem production. And while increased awareness about the many threats facing global fisheries seems to be gaining traction, the ocean, seas, lakes and rivers that support our scaled brethren are mostly invisible to us. Out of sight, out of mind. My hope was that this trip to America’s last frontier would be educational and inspiring, but most of all I was hoping to fall in love.

Nemo aside, fish are often cast as brainless, slimy and smelly characters in Earth’s ecosystem production. And while increased awareness about the many threats facing global fisheries seems to be gaining traction, the ocean, seas, lakes and rivers that support our scaled brethren are mostly invisible to us. Out of sight, out of mind. My hope was that this trip to America’s last frontier would be educational and inspiring, but most of all I was hoping to fall in love.

Resuscitating fish after their physical examination.

Sockeye salmon are anadromous, meaning they spend a portion of their lives in both fresh and salt water. Born in lakes and streams, Alaskan sockeye eventually swim to the nutrient rich sea where they grow and mature. That long journey and the biological metamorphosis it requires is impressive on its own, but what comes next is mind-boggling. When sockeye reach sexual maturity, they swim back home to spawn. And by “home” I’m not referring to a general geographic region, they swim precisely back to the lake or stream where they were born, and they do it by the millions.

Sockeye salmon are anadromous, meaning they spend a portion of their lives in both fresh and salt water. Born in lakes and streams, Alaskan sockeye eventually swim to the nutrient rich sea where they grow and mature. That long journey and the biological metamorphosis it requires is impressive on its own, but what comes next is mind-boggling. When sockeye reach sexual maturity, they swim back home to spawn. And by “home” I’m not referring to a general geographic region, they swim precisely back to the lake or stream where they were born, and they do it by the millions.

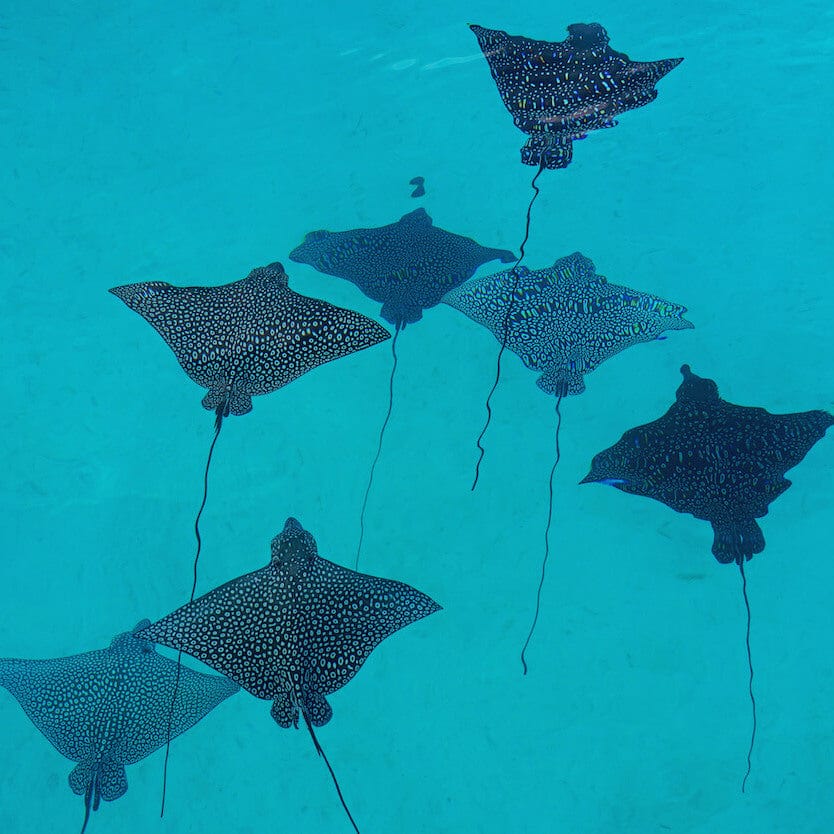

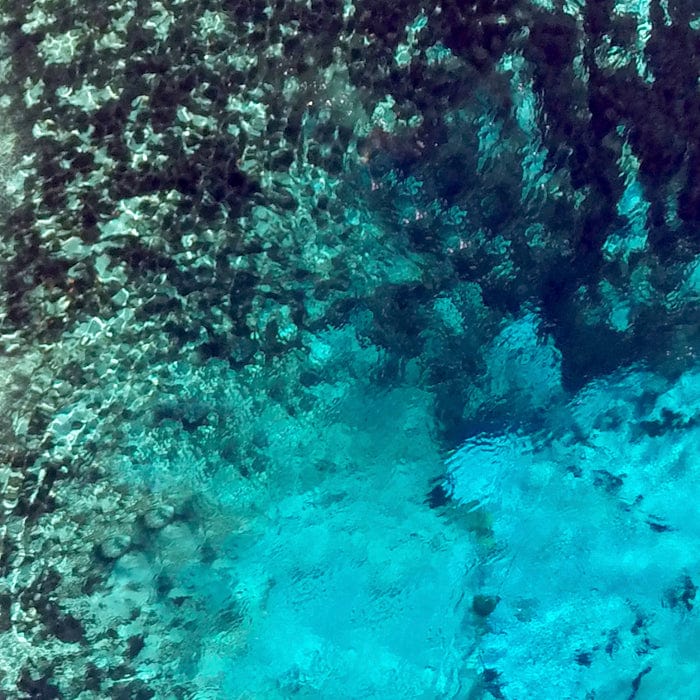

Thousands of Sockeye waiting outside the entrance of their home stream. These congregations attract various types of predators including bears, eagles and gulls.

All in all we spent ten days filming and observing the 2019 sockeye salmon run in southwestern Alaska. Our hosts and beneficiaries from our new apparel line were faculty, staff and students from the University of Washington’s Alaska Salmon Program. They have been coming here every summer since 1946 and noted that water levels this year were extremely low. Caused by reduced precipitation earlier in the season, low water levels can make it extremely challenging for sockeye to reach their spawning grounds.

All in all we spent ten days filming and observing the 2019 sockeye salmon run in southwestern Alaska. Our hosts and beneficiaries from our new apparel line were faculty, staff and students from the University of Washington’s Alaska Salmon Program. They have been coming here every summer since 1946 and noted that water levels this year were extremely low. Caused by reduced precipitation earlier in the season, low water levels can make it extremely challenging for sockeye to reach their spawning grounds.

Exploring streams along Lake Nerka. These study sites can only be reached by small boat or seaplane.

Standing along the banks of a small stream and watching sockeye drag themselves over rocks to reach their home while getting predated on by bears, eagles and gulls was an impactful moment I’ll never forget. These weren’t just fish, they were intelligent, tenacious, and fearless animals that refused to quit. Their struggle and fortitude was equal parts depressing and inspiring. But above all, it made me want to work harder in my own life and I loved them for that.

Standing along the banks of a small stream and watching sockeye drag themselves over rocks to reach their home while getting predated on by bears, eagles and gulls was an impactful moment I’ll never forget. These weren’t just fish, they were intelligent, tenacious, and fearless animals that refused to quit. Their struggle and fortitude was equal parts depressing and inspiring. But above all, it made me want to work harder in my own life and I loved them for that.

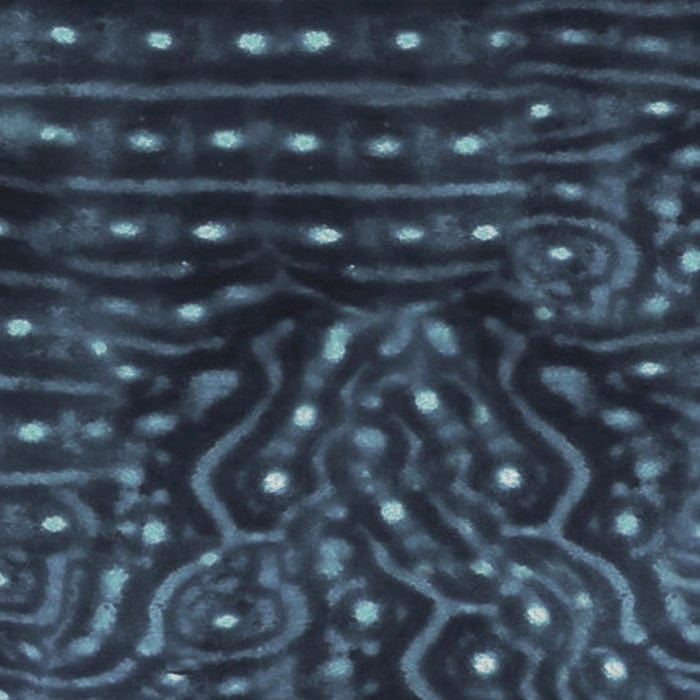

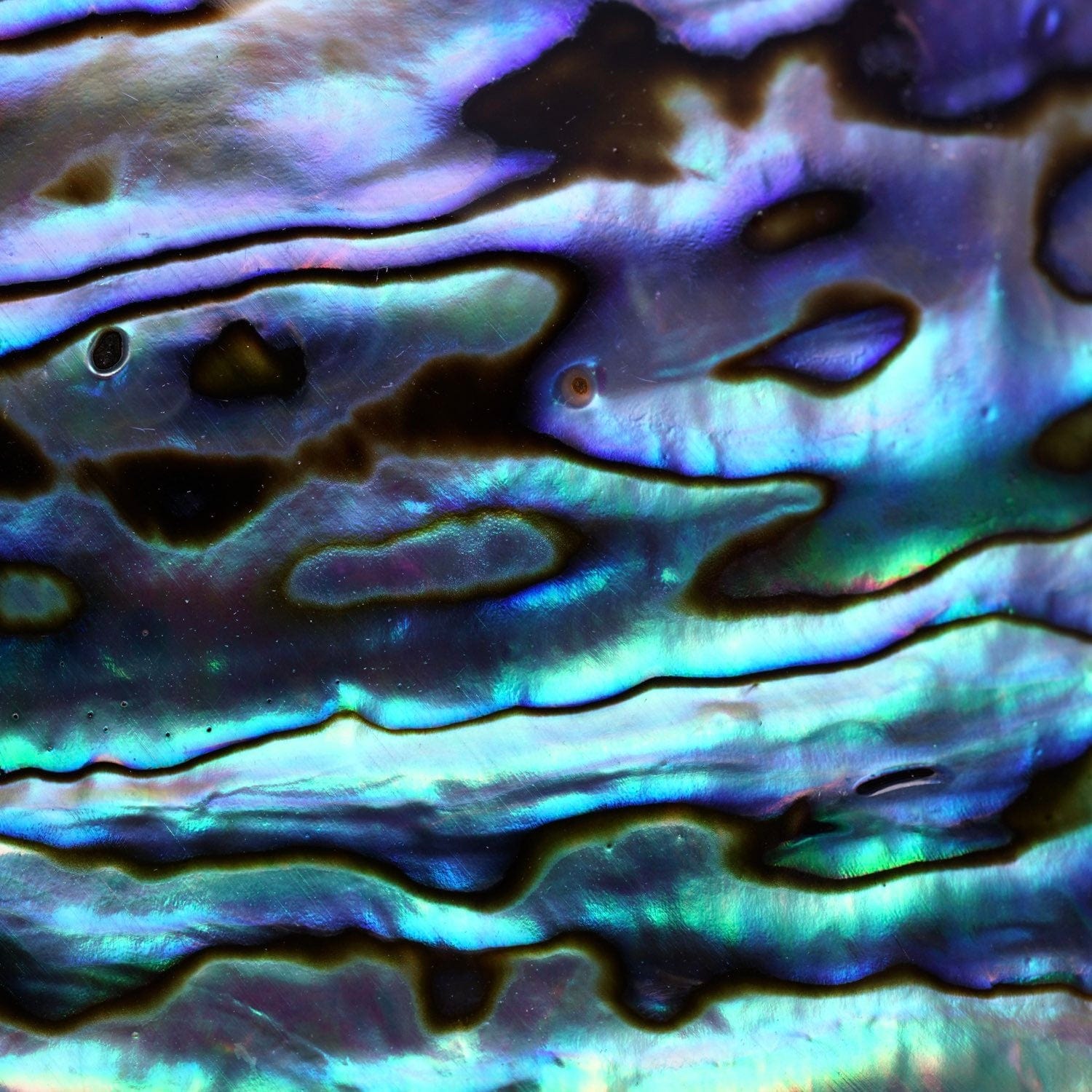

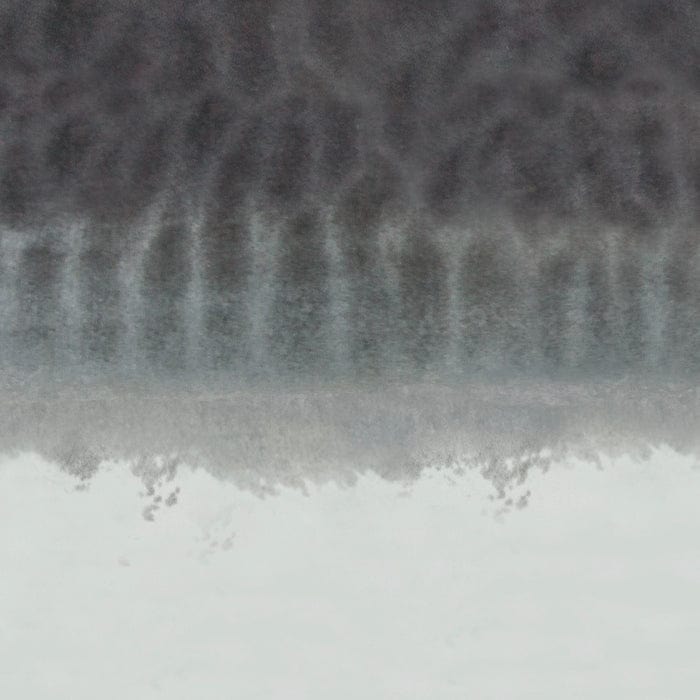

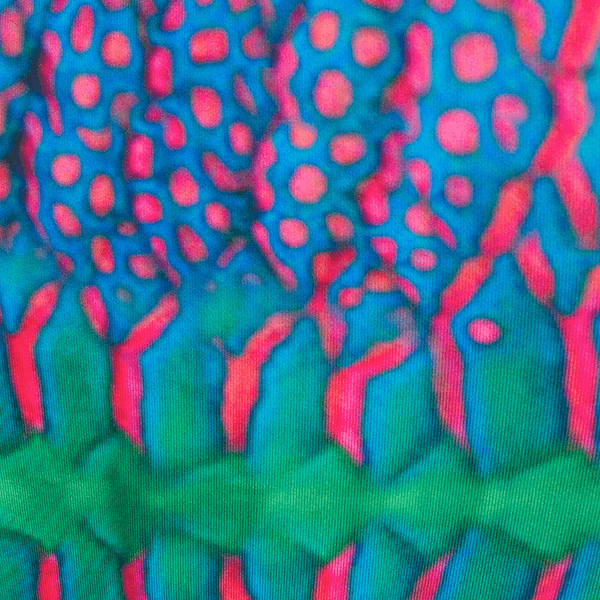

Sockeye are typically blue, but as they journey back to their freshwater spawning grounds their head turns green (top, left) and change shape, while the red-orange pigments from their flesh move to their skin, transforming the color of their bodies into a bright, brilliant red (top, right). Many fish are predated on before they are able to spawn. Gulls have developed an appetite for their eyeballs (bottom), eating them alive as they try to navigate through shallow waters.

Over the following months I would be tasked with piecing our team’s video footage from the trip together into a story that would hopefully make our audience, you, feel something. I wanted you to learn about UW’s amazing program, about the critically important research being done on this ecosystem and the lessons learned from the experts conducting it. But above all, I wanted you to feel like I did at that moment, that mixture of awe, grief, inspiration, and introspection. I wanted to make a film that challenges you to think critically and carefully about the species we share this planet with.

I wanted you to fall in love with a fish.

Over the following months I would be tasked with piecing our team’s video footage from the trip together into a story that would hopefully make our audience, you, feel something. I wanted you to learn about UW’s amazing program, about the critically important research being done on this ecosystem and the lessons learned from the experts conducting it. But above all, I wanted you to feel like I did at that moment, that mixture of awe, grief, inspiration, and introspection. I wanted to make a film that challenges you to think critically and carefully about the species we share this planet with.

I wanted you to fall in love with a fish.

Patrick Rynne is the CEO and Founder of Waterlust.

PhD in marine physics and a masters in Ocean Engineering. Hates spreadsheets but is learning to live with them. Avid kiter, sailor, surfer and teller of stories. Frequent wearer of flip flops in socially inappropriate settings.

Leave a comment (all fields required)