Typically, SCUBA diving is peaceful and quiet. The only sound is your own breath. But on that day, in the idyllic marine habitat off Miami Beach, the very reef that makes this part of the world iconic, was darkened with swirling sediment clouds. The ocean floor was gray and flat -- the reef looked more like a moonscape than a vibrant and functioning ecosystem. All of the reef’s colors and its natural nooks and crannies were covered by fine sediments that fell like a volcano’s ash onto everything that lay below. Something was clearly very wrong. As we dove, the current was ripping through the nearby shipping channel, requiring all of our strength to search for the threatened staghorn corals in the area. A constant whirring and crunching sound nearby was so loud that it caused vibrations that shook our chests. It was 2015, and although I had been a scientific diver for nearly a decade, this was unlike anything I had experienced before. Diving next to an active dredging operation was a new and intense experience.

Typically, SCUBA diving is peaceful and quiet. The only sound is your own breath. But on that day, in the idyllic marine habitat off Miami Beach, the very reef that makes this part of the world iconic, was darkened with swirling sediment clouds. The ocean floor was gray and flat -- the reef looked more like a moonscape than a vibrant and functioning ecosystem. All of the reef’s colors and its natural nooks and crannies were covered by fine sediments that fell like a volcano’s ash onto everything that lay below. Something was clearly very wrong. As we dove, the current was ripping through the nearby shipping channel, requiring all of our strength to search for the threatened staghorn corals in the area. A constant whirring and crunching sound nearby was so loud that it caused vibrations that shook our chests. It was 2015, and although I had been a scientific diver for nearly a decade, this was unlike anything I had experienced before. Diving next to an active dredging operation was a new and intense experience.

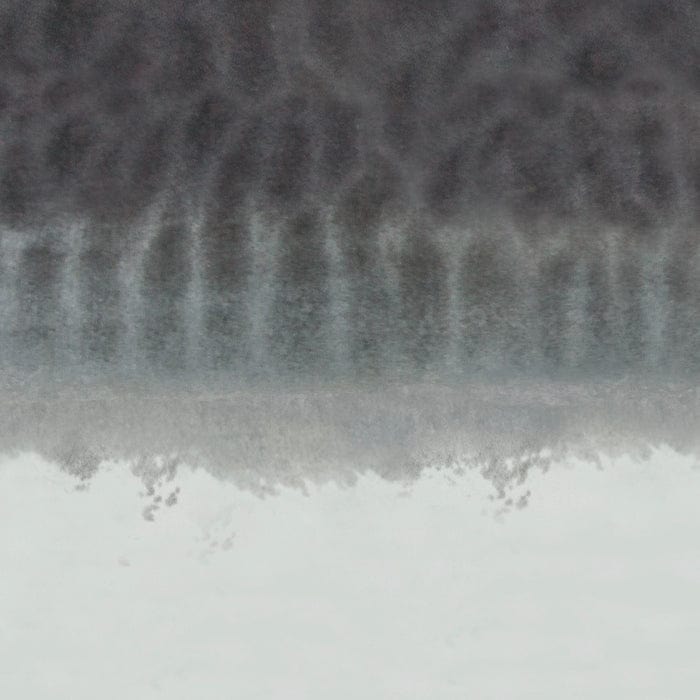

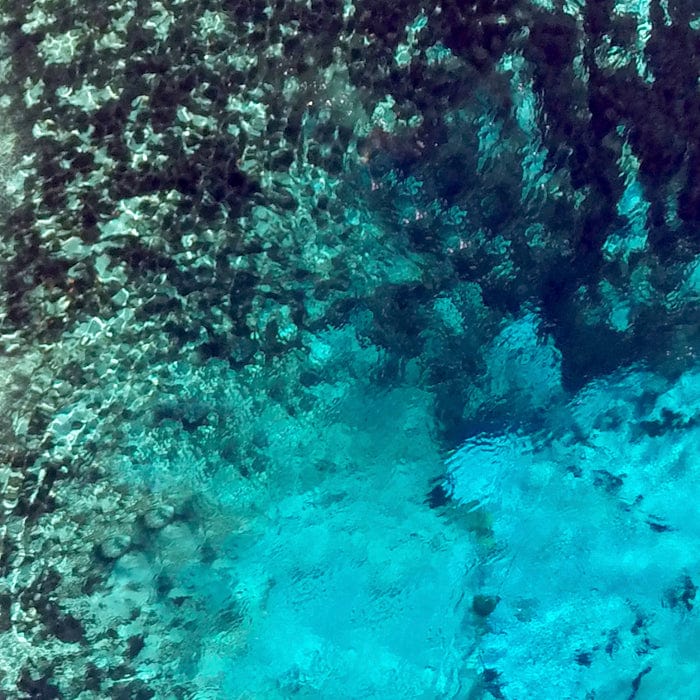

Diving through clouds of sediment kicked up from the nearby dredging project, it slowly became clear that the moonscape we were swimming over used to be Miami's thriving coral reef. (Photo credit: Pete Zuccarini)

Before I go deeper into how I found myself hovering over an apocalyptic seascape with industrial machinery blaring through the water column, I should probably introduce myself. My name is Dr. Rachel Silverstein, I have a Ph.D. in Marine Biology and Fisheries from the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences. After graduating, I undertook a Knauss Sea Grant Fellowship with the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee in Washington, D.C. In that unique program, I got a crash course on the federal legislative process and the role of science in policy. It also inspired me to want to come back to Miami and use science to be a champion for the reefs that I had mapped and monitored during graduate school. In June 2014, I started as Executive Director and Waterkeeper at the small non-profit organization, then Biscayne Bay Waterkeeper, where I was the only staff member (we now have 7 staff!). We changed our name to Miami Waterkeeper, the “waterkeeper” moniker a key feature of the name, as we are members of the international network of water advocates, the Waterkeeper Alliance. A waterkeeper is a job that is unique to groups within that Alliance, and it means a person who is a designated spokesperson for a particular body of water, a mix of scientist, advocate, and educator.

Before I go deeper into how I found myself hovering over an apocalyptic seascape with industrial machinery blaring through the water column, I should probably introduce myself. My name is Dr. Rachel Silverstein, I have a Ph.D. in Marine Biology and Fisheries from the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences. After graduating, I undertook a Knauss Sea Grant Fellowship with the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee in Washington, D.C. In that unique program, I got a crash course on the federal legislative process and the role of science in policy. It also inspired me to want to come back to Miami and use science to be a champion for the reefs that I had mapped and monitored during graduate school. In June 2014, I started as Executive Director and Waterkeeper at the small non-profit organization, then Biscayne Bay Waterkeeper, where I was the only staff member (we now have 7 staff!). We changed our name to Miami Waterkeeper, the “waterkeeper” moniker a key feature of the name, as we are members of the international network of water advocates, the Waterkeeper Alliance. A waterkeeper is a job that is unique to groups within that Alliance, and it means a person who is a designated spokesperson for a particular body of water, a mix of scientist, advocate, and educator.

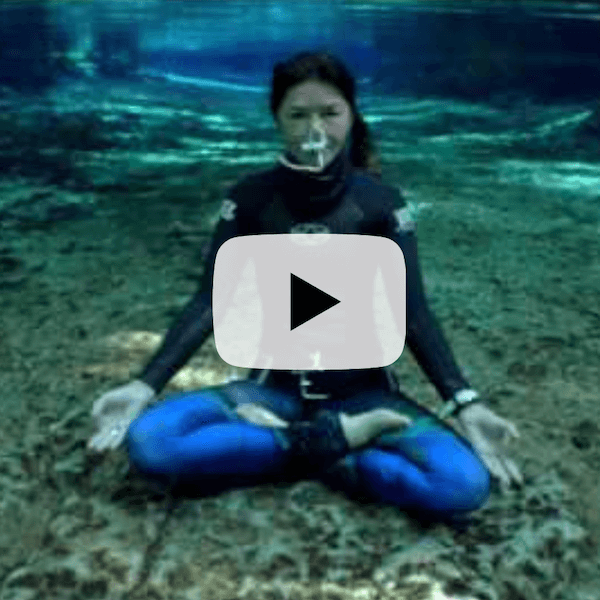

I got to dive in submersibles with Philippe Cousteau to raise awareness about the reefs at risk from the upcoming dredging of Port Everglades. Because of our litigation, that project has already been delayed for several years while the environmental assessments are redone to be more protective of corals. The new documents are going to be released in December 2020, and the public will have a chance to weigh in! (Photo credit: Katie Cleary)

It was my 4th day on the job at Miami Waterkeeper when I got a call from the media asking about the PortMiami expansion project, an engineering initiative to deepen Miami’s primary shipping channel to facilitate larger shipping vessels. The region being dredged crossed the Florida reef tract -- the only nearshore coral reef in the continental United States -- a vibrant coral reef once filled with Endangered Species Act listed staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis), and scientists and residents were concerned that adequate precautions were not being taken to protect it. The project was being overseen by the Army Corps of Engineers, an engineering branch of the Army that, since 1775, has tackled large scale civil works projects in the United States. One of many environmental requisites of the project was that no staghorn corals were to be harmed in the project and that nearby corals would be impacted only “insignificantly”. My organization had also challenged the permit of the project before I started. To make sure that they were adhering to the requirements of the project, we had decided to dive the site and see for ourselves.

It was my 4th day on the job at Miami Waterkeeper when I got a call from the media asking about the PortMiami expansion project, an engineering initiative to deepen Miami’s primary shipping channel to facilitate larger shipping vessels. The region being dredged crossed the Florida reef tract -- the only nearshore coral reef in the continental United States -- a vibrant coral reef once filled with Endangered Species Act listed staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis), and scientists and residents were concerned that adequate precautions were not being taken to protect it. The project was being overseen by the Army Corps of Engineers, an engineering branch of the Army that, since 1775, has tackled large scale civil works projects in the United States. One of many environmental requisites of the project was that no staghorn corals were to be harmed in the project and that nearby corals would be impacted only “insignificantly”. My organization had also challenged the permit of the project before I started. To make sure that they were adhering to the requirements of the project, we had decided to dive the site and see for ourselves.

Miami's reef was turned into a moonscape by the sediment churned up during dredging. The sediment smothered the corals and buried the reef habitat. We dove in difficult conditions to document as much damage as we could. (Photo credit: Pete Zuccarini)

Staghorn corals are an important species that are rapidly disappearing from Florida’s reefs. It’s estimated that 98% of these corals are already gone, which prompted their listing as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2006 -- one of the first two corals ever to be listed. Staghorn corals have interlocking branches, which provide important places for fish to live. Overall, Florida’s coral reef has declined by over 80% since the 1970s.

Suspended sediments from dredging might not seem like a big deal, but for a coral, they can be deadly. Corals are very unique creatures. They may look like rocks, but they’re actually animals that build hard skeletons. They also have single-celled algae living in their tissues, and get energy from the sun, just like a plant! When there’s too much sediment in the water, corals get shaded and they can’t get the sunlight they need to survive. The sediment in the water also eventually can land on the ocean floor and smother the corals living there.

Staghorn corals are an important species that are rapidly disappearing from Florida’s reefs. It’s estimated that 98% of these corals are already gone, which prompted their listing as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2006 -- one of the first two corals ever to be listed. Staghorn corals have interlocking branches, which provide important places for fish to live. Overall, Florida’s coral reef has declined by over 80% since the 1970s.

Suspended sediments from dredging might not seem like a big deal, but for a coral, they can be deadly. Corals are very unique creatures. They may look like rocks, but they’re actually animals that build hard skeletons. They also have single-celled algae living in their tissues, and get energy from the sun, just like a plant! When there’s too much sediment in the water, corals get shaded and they can’t get the sunlight they need to survive. The sediment in the water also eventually can land on the ocean floor and smother the corals living there.

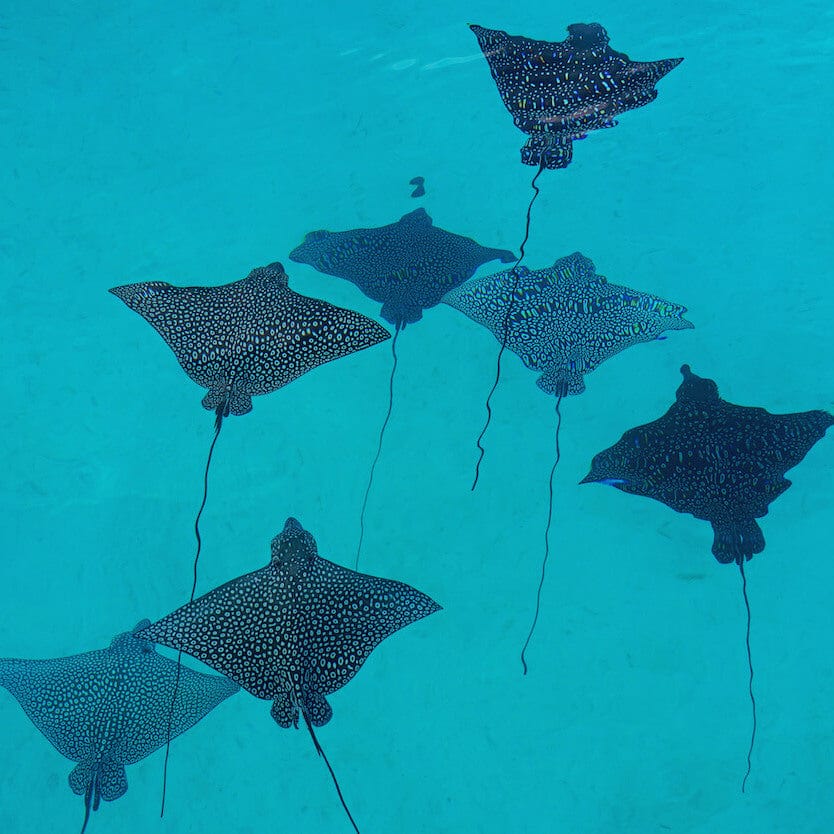

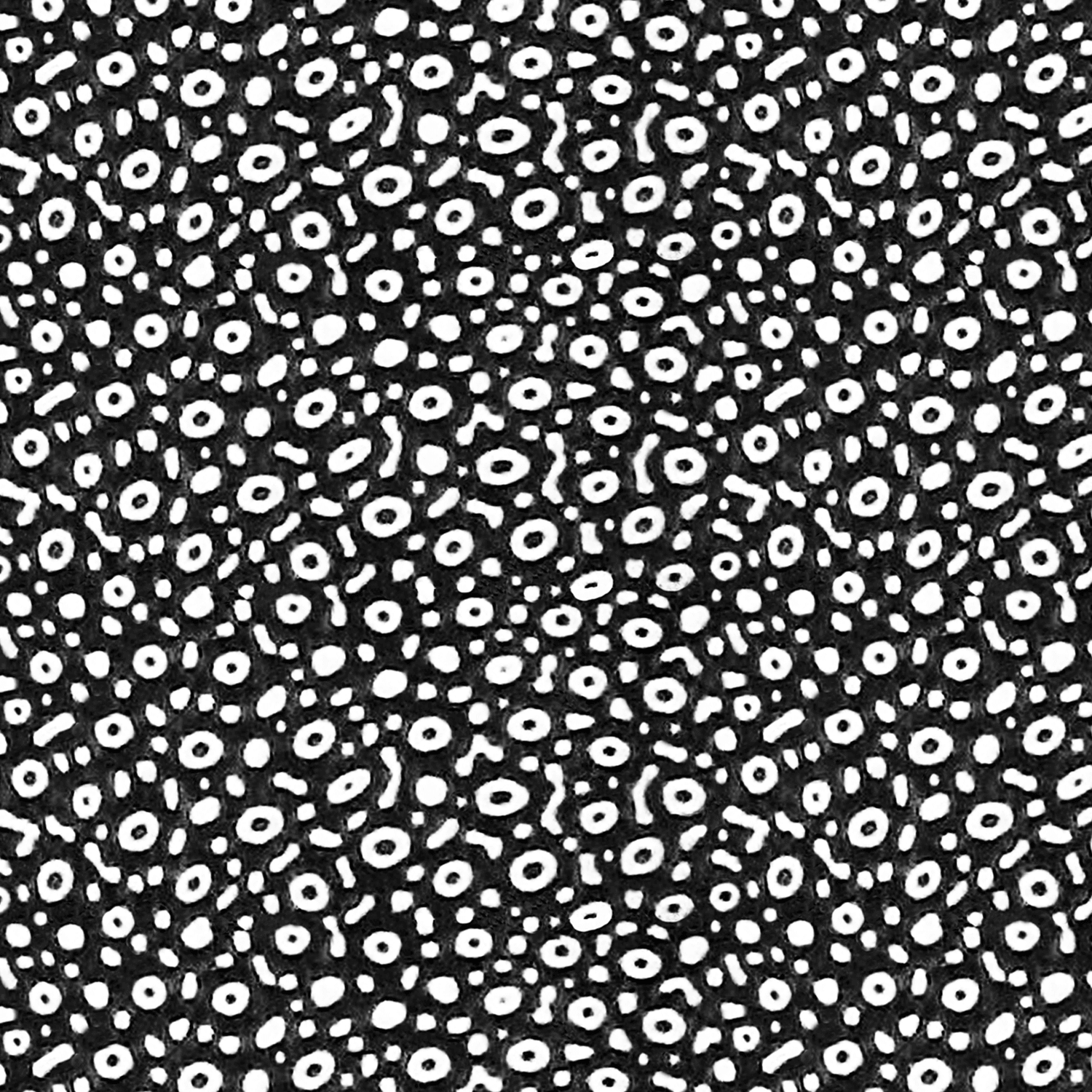

Staghorn corals have long branches like antlers. They grow close together and form "thickets" like these, which provide crucial habitat for fish and other wildlife. Florida used to have miles of staghorn thickets like these, but NOAA now estimates that over 98% of these corals have been lost. Along with elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata), they were the first corals listed under the Endangered Species Act in 2006.

Kicking up sediment is inevitable when dredging, so to regulate it, sediment levels are restricted to certain amounts to avoid harm to the reef. Yet on that fateful day we discovered that corals were, indeed, being buried and smothered by sediment from the dredging -- including the protected staghorn corals. I figured it was all a big misunderstanding, that I could call the Army Corps and let them know about the coral that was being harmed, and of course, they would stop. But a few weeks later, after some major runarounds and stonewalling from the agency, we quickly launched into what would be a 4-year-long battle to protect our corals -- and a crash course for me on the power of individuals to protect our environment.

If you had asked me as a marine science graduate student if I would ever sue the federal government, I would have laughed at you! As a scientist, I had never before fully appreciated the role that our legal system has in conservation-- or the intersection of science with law and policy. When Congress passed many of our seminal environmental laws, like the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act, they envisioned that citizens would play a key role in ensuring that these laws met their full potential. They gave us the power to bring “citizen suits,” in which individuals (or groups representing individuals) who have been harmed by pollution can actually step into the role of an enforcement agency and bring polluters to Court -- even the federal government!

Kicking up sediment is inevitable when dredging, so to regulate it, sediment levels are restricted to certain amounts to avoid harm to the reef. Yet on that fateful day we discovered that corals were, indeed, being buried and smothered by sediment from the dredging -- including the protected staghorn corals. I figured it was all a big misunderstanding, that I could call the Army Corps and let them know about the coral that was being harmed, and of course, they would stop. But a few weeks later, after some major runarounds and stonewalling from the agency, we quickly launched into what would be a 4-year-long battle to protect our corals -- and a crash course for me on the power of individuals to protect our environment.

If you had asked me as a marine science graduate student if I would ever sue the federal government, I would have laughed at you! As a scientist, I had never before fully appreciated the role that our legal system has in conservation-- or the intersection of science with law and policy. When Congress passed many of our seminal environmental laws, like the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act, they envisioned that citizens would play a key role in ensuring that these laws met their full potential. They gave us the power to bring “citizen suits,” in which individuals (or groups representing individuals) who have been harmed by pollution can actually step into the role of an enforcement agency and bring polluters to Court -- even the federal government!

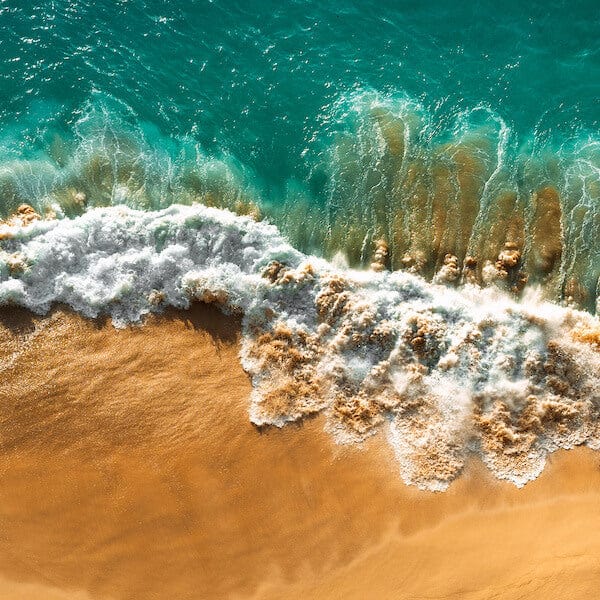

The dredging ship has a "cutterhead", which looks like a giant eggbeater with spikes, and cuts through the rock and reef. A massive suction tube then sucks up the rock and sediment into a barge to transport it offshore. Unfortunately, they also leaked water that was full of fine sediment right on top of the reef, which resulted in the burial of over 500,000 corals. Diving nearby the dredging, it sounded like someone was eating a car. We could feel the vibrations from the cutterhead operation. (Photo credit: Tom Fitz)

By bringing litigation with our fearless legal team, and spending thousands and thousands of hours working on legal documents, diving for evidence, and publishing scientific studies, we were able to secure the restoration of over 10,000 threatened corals in Miami-Dade county, among other wins. We also uncovered several misleading or outright false claims from the Army Corps -- including a photo of a supposedly healthy staghorn coral allegedly taken near the dredging site that they entered into evidence. But we found the photo online and determined that it was taken in 1992 in the Cayman Islands! Eventually, one of the primary Army Corps staff on the project pled guilty of lying to federal investigators. We are now working to ensure that the same catastrophe doesn’t repeat itself at Port Everglades, just 30 miles north. They are planning to expand the shipping channel there too -- and just like Miami, it crosses the reef tract. The Army Corps failed to update their environmental plans for the project after the disaster that happened in Miami, so we brought additional litigation and we were able to force a reassessment of the environmental risks, which has already delayed the project by several years. The new documents are slated to be released this coming December.

By bringing litigation with our fearless legal team, and spending thousands and thousands of hours working on legal documents, diving for evidence, and publishing scientific studies, we were able to secure the restoration of over 10,000 threatened corals in Miami-Dade county, among other wins. We also uncovered several misleading or outright false claims from the Army Corps -- including a photo of a supposedly healthy staghorn coral allegedly taken near the dredging site that they entered into evidence. But we found the photo online and determined that it was taken in 1992 in the Cayman Islands! Eventually, one of the primary Army Corps staff on the project pled guilty of lying to federal investigators. We are now working to ensure that the same catastrophe doesn’t repeat itself at Port Everglades, just 30 miles north. They are planning to expand the shipping channel there too -- and just like Miami, it crosses the reef tract. The Army Corps failed to update their environmental plans for the project after the disaster that happened in Miami, so we brought additional litigation and we were able to force a reassessment of the environmental risks, which has already delayed the project by several years. The new documents are slated to be released this coming December.

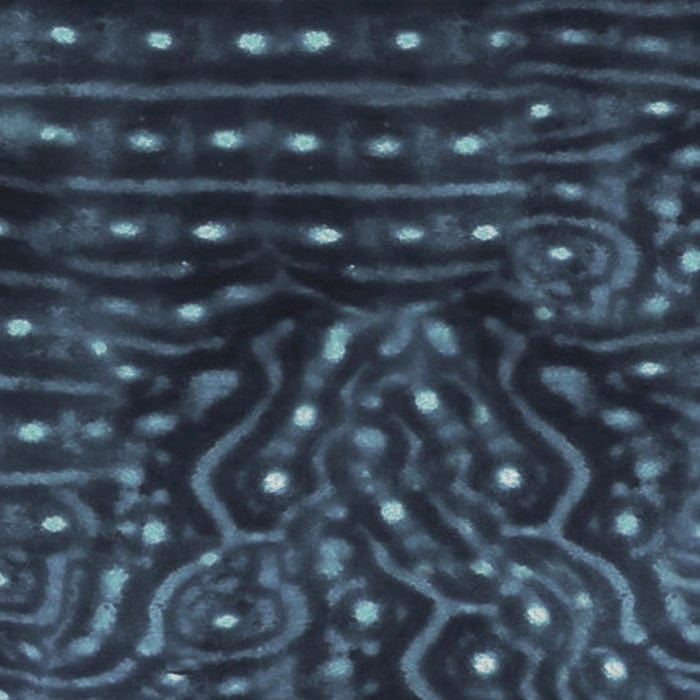

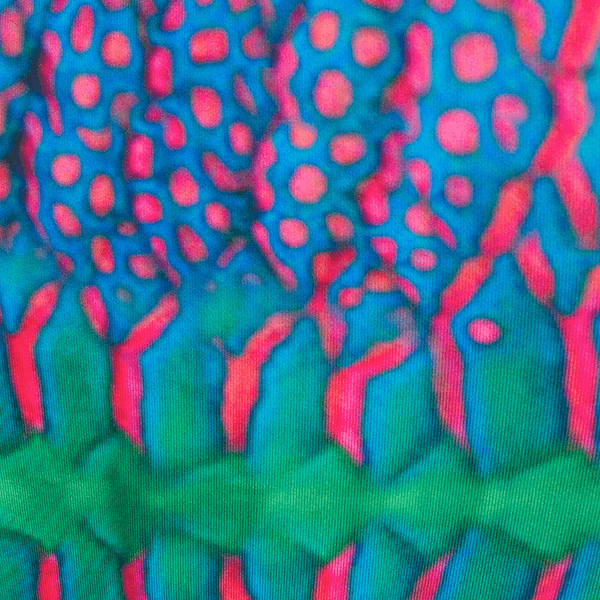

An Orbicella coral in happier times. This nearby reef was not impacted by dredging. These corals were listed in 2014 as threatened on the Endangered Species Act. (Photo credit: Rivah Winter)

The PortMiami project was just one of the many legal actions we’ve taken as an organization in our ten years. Like all of our campaigns, our work is squarely rooted in sound science. For example, the dredging company’s contractors concluded that the dredging project killed only six corals. Total! We spent a year analyzing their data (obtained through records request laws, which required litigation too!), and we published peer-reviewed literature showing that at least 560,000 corals were harmed. We intend that this study will help guide the restoration of this and other reefs like it and highlight the important role that science plays in large scale civil projects. Science is what gives us the power to take action to protect the environment.

Jumping into the murky water next to the dredge ship that day was risky, and so was taking on the Army Corps in federal court. Although Miami Waterkeeper and our partners were entering a David versus Goliath battle, the strong foundation of the science and the power of our environmental laws helped us to stand up to something much bigger and more powerful than ourselves.

I encourage all of you who love the outdoors to find your own power wherever you are. There are ways to protect the environment (or community) that you love, and your voice is a crucial part of the system working properly. At Miami Waterkeeper, we seek to empower the community to protect your own environment. No matter where you are, dig in, learn, volunteer, follow the science, and make a difference.

The PortMiami project was just one of the many legal actions we’ve taken as an organization in our ten years. Like all of our campaigns, our work is squarely rooted in sound science. For example, the dredging company’s contractors concluded that the dredging project killed only six corals. Total! We spent a year analyzing their data (obtained through records request laws, which required litigation too!), and we published peer-reviewed literature showing that at least 560,000 corals were harmed. We intend that this study will help guide the restoration of this and other reefs like it and highlight the important role that science plays in large scale civil projects. Science is what gives us the power to take action to protect the environment.

Jumping into the murky water next to the dredge ship that day was risky, and so was taking on the Army Corps in federal court. Although Miami Waterkeeper and our partners were entering a David versus Goliath battle, the strong foundation of the science and the power of our environmental laws helped us to stand up to something much bigger and more powerful than ourselves.

I encourage all of you who love the outdoors to find your own power wherever you are. There are ways to protect the environment (or community) that you love, and your voice is a crucial part of the system working properly. At Miami Waterkeeper, we seek to empower the community to protect your own environment. No matter where you are, dig in, learn, volunteer, follow the science, and make a difference.

Dr. Rachel Silverstein is the Executive Director and Waterkeeper of the non-profit organization Miami Waterkeeper. She has a Ph.D. in Marine Biology and Fisheries from University of Miami's Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science with a research focus on the effect of climate change on reef corals. Dr. Silverstein graduated cum laude in 2006 from Columbia University with a B.S. degree in Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology and was a Knauss Sea Grant Fellow with the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee. You can follow and support her work at www.miamiwaterkeeper.org

Marva Sletten

May 31, 2021

Rachel, thank you so much for the crucial work you are doing. It is heartening to know that such knowledgeable and dedicated professionals are out there working hard to counter the assault on this amazing natural resource.