1.5 hours generator run-time, every-other-day, means we have 1.5 years of diesel fuel aboard, in the most optimistic scenario.

Propane, not as generous, 10 lb tank per 4 weeks, 17 lbs remain, which equates to 6.8 more weeks of essential cooking gas.

Rice: 17 lbs

Flour: 25 lbs

Beans: 5 lbs

Cooking oil: 2.5 liters

I keep lists of everything.

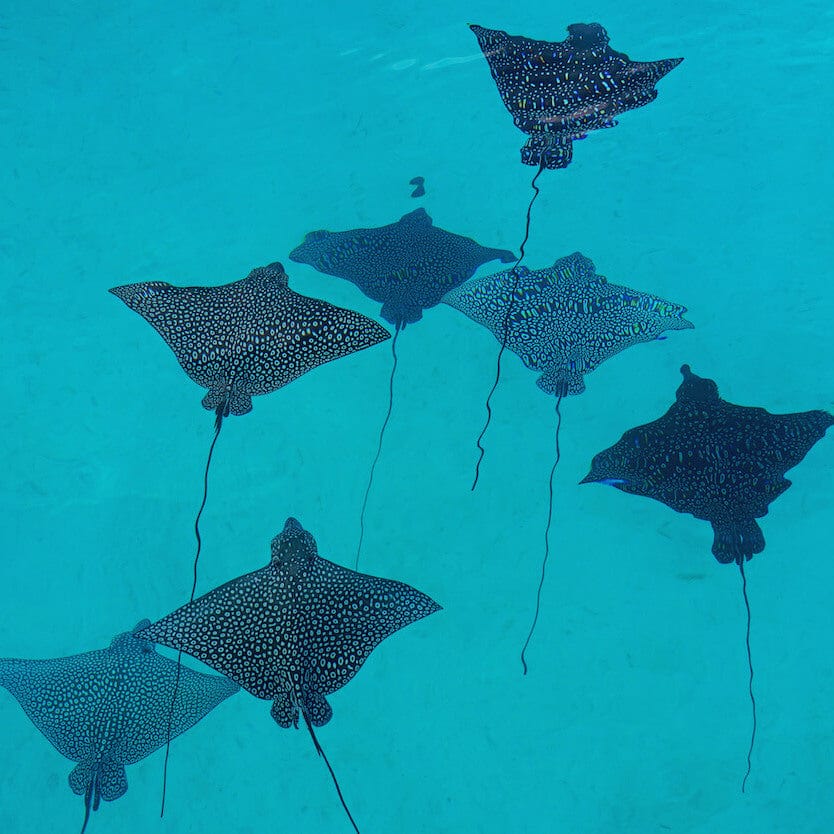

We are having more rice and seafood than we ever have, thanks to relatively healthy nearby reefs and a well-stocked collection of non-perishables. But despite these food-extending efforts, one day we will run low on supplies. These are the kinds of thoughts that zip through my head daily as we navigate a global pandemic on a sailboat stuck in a desolate corner of the Caribbean.

My name is Conor Smith, and like everyone, my life has changed dramatically in recent months. My fiancé, Stephanie, and I live aboard our sailboat full time and had plans to be logging 2,000 nautical miles under her keel by the summertime. Instead we are seeking isolated anchorages in the remote Bahamas to remain safe during these unsure times. We are looking to minimize exposure to other people and have a war-like mindset to reduce our consumption of supplies and fuel to extend the working life of everything we have aboard.

1.5 hours generator run-time, every-other-day, means we have 1.5 years of diesel fuel aboard, in the most optimistic scenario.

Propane, not as generous, 10 lb tank per 4 weeks, 17 lbs remain, which equates to 6.8 more weeks of essential cooking gas.

Rice: 17 lbs

Flour: 25 lbs

Beans: 5 lbs

Cooking oil: 2.5 liters

I keep lists of everything.

We are having more rice and seafood than we ever have, thanks to relatively healthy nearby reefs and a well-stocked collection of non-perishables. But despite these food-extending efforts, one day we will run low on supplies. These are the kinds of thoughts that zip through my head daily as we navigate a global pandemic on a sailboat stuck in a desolate corner of the Caribbean.

My name is Conor Smith, and like everyone, my life has changed dramatically in recent months. My fiancé, Stephanie, and I live aboard our sailboat full time and had plans to be logging 2,000 nautical miles under her keel by the summertime. Instead we are seeking isolated anchorages in the remote Bahamas to remain safe during these unsure times. We are looking to minimize exposure to other people and have a war-like mindset to reduce our consumption of supplies and fuel to extend the working life of everything we have aboard.

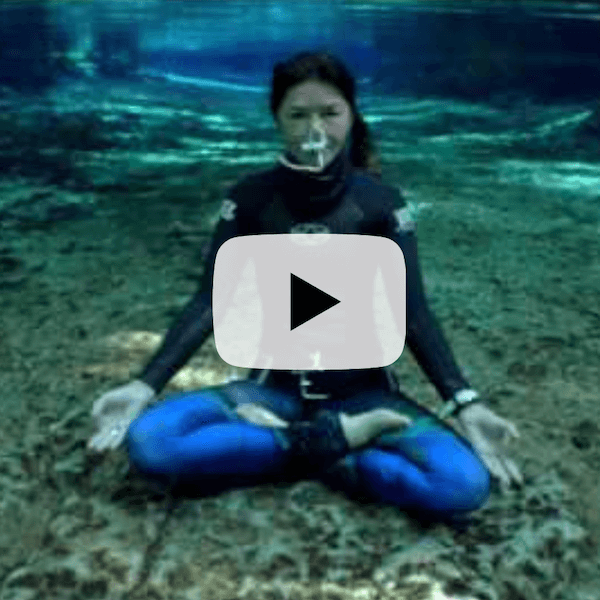

Stephanie and I on an early date in our relationship.

Stephanie and I on an early date in our relationship.

Typically, I find that the challenges associated with provisioning and maintaining life aboard a boat are significantly different than those in a house or apartment. But today, it feels like those differences are blurry. If you’re like most folks, you’re probably stuck at home, and like me, you may be keeping track of dwindling resources and planning how to acquire more. You may find yourself running through worst-case scenarios and setting up mental contingency plans. If you’re fortunate enough to still be employed, you might try and establish a routine to keep productivity up. Maybe you realize the routine gets old quick, and without finding ways to truly blow off a little steam, morale of the crew ebbs and flows. You are in quarantine, and it’s hard.

Typically, I find that the challenges associated with provisioning and maintaining life aboard a boat are significantly different than those in a house or apartment. But today, it feels like those differences are blurry. If you’re like most folks, you’re probably stuck at home, and like me, you may be keeping track of dwindling resources and planning how to acquire more. You may find yourself running through worst-case scenarios and setting up mental contingency plans. If you’re fortunate enough to still be employed, you might try and establish a routine to keep productivity up. Maybe you realize the routine gets old quick, and without finding ways to truly blow off a little steam, morale of the crew ebbs and flows. You are in quarantine, and it’s hard.

It’s amazing how quickly things can change. Pre-Corona times traveling in the San Blas islands of Panamá.

Quarantine, you can’t go 5 minutes without hearing it these days. This salty word, brimming with nautical heritage, has made its way into land life and repeated in unprecedented levels. While sailors are as accustomed to this word as much as rum and soda, it seems oddly out of place and incompatible with modern verbiage ashore.

Whenever a vessel arrives to another country, the custom is to raise the internationally recognized“Q” flag, which indicates the vessel is arriving from another country, has not yet completed official paperwork, and therefore the crew is required to remain aboard while the captain contacts the necessary officials. The crew are forbidden to disembark the ship until all paperwork and inspections have occurred. Part of the reasoning for this process is to ensure that diseases are contained aboard the ship and not transferred to their host country. This was of critical importance in the early days of sailing, when water travel was the only means of connecting continents and disease was only spread through ships. Look at the etymology of quarantine:‘quint’, in Italian, referred to the forty day period a ship’s crew were required to stay isolated aboard the vessel before allowed ashore. This period allowed any possible disease to run its course.

Quarantine, you can’t go 5 minutes without hearing it these days. This salty word, brimming with nautical heritage, has made its way into land life and repeated in unprecedented levels. While sailors are as accustomed to this word as much as rum and soda, it seems oddly out of place and incompatible with modern verbiage ashore.

Whenever a vessel arrives to another country, the custom is to raise the internationally recognized“Q” flag, which indicates the vessel is arriving from another country, has not yet completed official paperwork, and therefore the crew is required to remain aboard while the captain contacts the necessary officials. The crew are forbidden to disembark the ship until all paperwork and inspections have occurred. Part of the reasoning for this process is to ensure that diseases are contained aboard the ship and not transferred to their host country. This was of critical importance in the early days of sailing, when water travel was the only means of connecting continents and disease was only spread through ships. Look at the etymology of quarantine:‘quint’, in Italian, referred to the forty day period a ship’s crew were required to stay isolated aboard the vessel before allowed ashore. This period allowed any possible disease to run its course.

Hoisting the "Q" flag in a foreign country.

Health concerns are usually of lesser importance to officials in modern times (pre-Coronavirus), but still, every clearance form has a dedicated page of questions pertaining to the health of the crew, called (in one way or another) The Maritime Declaration of Health. It asks questions, as simple as how large is the holding tank of the vessel, to as grim as how many deaths have occurred since the last port. Some countries have a dedicated official that administers this portion of the form, while others only give a cursory glance. How will this change in a post pandemic world? No one knows yet.

Health concerns are usually of lesser importance to officials in modern times (pre-Coronavirus), but still, every clearance form has a dedicated page of questions pertaining to the health of the crew, called (in one way or another) The Maritime Declaration of Health. It asks questions, as simple as how large is the holding tank of the vessel, to as grim as how many deaths have occurred since the last port. Some countries have a dedicated official that administers this portion of the form, while others only give a cursory glance. How will this change in a post pandemic world? No one knows yet.

Our signed Declaration of Health from Jamaica.

Living on a boat in quarantine in an isolated place is difficult, I’m not going to lie. As sailors that explore remote parts of the planet, Stephanie and I have extensive experience dealing with isolation, self-sufficiency, and social distancing. As I write this, we have been living in the same 250 (oddly-shaped) square feet for the last six months and three days, with the longest separation only five hours long, which occurred when I missed my water taxi after a shopping and provisioning trip ashore. But despite our experience, this global pandemic is challenging us, as I’m sure it’s challenging you, in both logistical and emotional ways.

Some may find our logistical challenges interesting, or at least entertaining, so here is a rundown of life aboard Grace. We are currently in one of the remote island chains of the Bahamas, called the Ragged Islands. The cruising guide states,“The Ragged Islands…[are a] unpopulated wilderness with only one tiny settlement, closer to Cuba than Georgetown [the next closest Bahamian city]. You must be totally self sufficient here.” This remote region hosts Bahamian fisherman and experienced sailors. The only settlement had a peak population of about 100 residents before Hurricane Irma ravaged the island and encouraged many residents to leave. Now, the only market on the island, run by a woman named Maria, is partially closed because she is stuck off-island and can’t return because the mail boat is forbidden from carrying passengers.

Living on a boat in quarantine in an isolated place is difficult, I’m not going to lie. As sailors that explore remote parts of the planet, Stephanie and I have extensive experience dealing with isolation, self-sufficiency, and social distancing. As I write this, we have been living in the same 250 (oddly-shaped) square feet for the last six months and three days, with the longest separation only five hours long, which occurred when I missed my water taxi after a shopping and provisioning trip ashore. But despite our experience, this global pandemic is challenging us, as I’m sure it’s challenging you, in both logistical and emotional ways.

Some may find our logistical challenges interesting, or at least entertaining, so here is a rundown of life aboard Grace. We are currently in one of the remote island chains of the Bahamas, called the Ragged Islands. The cruising guide states,“The Ragged Islands…[are a] unpopulated wilderness with only one tiny settlement, closer to Cuba than Georgetown [the next closest Bahamian city]. You must be totally self sufficient here.” This remote region hosts Bahamian fisherman and experienced sailors. The only settlement had a peak population of about 100 residents before Hurricane Irma ravaged the island and encouraged many residents to leave. Now, the only market on the island, run by a woman named Maria, is partially closed because she is stuck off-island and can’t return because the mail boat is forbidden from carrying passengers.

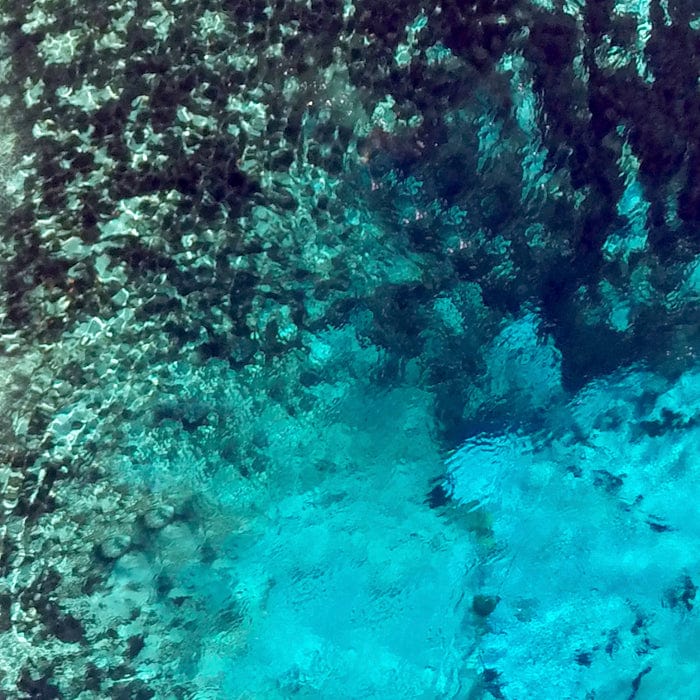

Google maps satellite view of the Ragged Islands, Bahamas.

The Bahamian government is consistent with most nations’efforts to practice quarantining and social isolation. The Bahamas, with 700 islands and 2,000 cays, is a water nation where the primary means of travel is still ship-based, therefore isolating islands requires closing stores and shutting down inter-island travel. The hundreds of cruising boats that flock to these sun-drenched islands each winter season are now required to stay put and not move between island groups, except for essential travel.

In remote islands, weather is the driving factor in where we anchor and when we move. All of these anchorages have only partial directional wind/wave protection, so as cold fronts come down from the cold northern latitudes, and the winds change direction from the usual easterlies, we are forced to move anchorages, sometimes three times per day, depending on the instantaneous and forecast wind direction. While we are under a strict order from the Bahamian Prime Minister to not move our vessel, no official thinks twice when a sailboat pulls anchor and moves around a corner to find better protection for upcoming winds. There is a higher order in place: respect for mother natures’winds and waves. When officials make orders, they design them for civilization: locally in remote islands, devoid of assistance, they are interpreted for intent.

The Bahamian government is consistent with most nations’efforts to practice quarantining and social isolation. The Bahamas, with 700 islands and 2,000 cays, is a water nation where the primary means of travel is still ship-based, therefore isolating islands requires closing stores and shutting down inter-island travel. The hundreds of cruising boats that flock to these sun-drenched islands each winter season are now required to stay put and not move between island groups, except for essential travel.

In remote islands, weather is the driving factor in where we anchor and when we move. All of these anchorages have only partial directional wind/wave protection, so as cold fronts come down from the cold northern latitudes, and the winds change direction from the usual easterlies, we are forced to move anchorages, sometimes three times per day, depending on the instantaneous and forecast wind direction. While we are under a strict order from the Bahamian Prime Minister to not move our vessel, no official thinks twice when a sailboat pulls anchor and moves around a corner to find better protection for upcoming winds. There is a higher order in place: respect for mother natures’winds and waves. When officials make orders, they design them for civilization: locally in remote islands, devoid of assistance, they are interpreted for intent.

A strong squall approaching in the afternoon. These are much better weathered during the day than at night.

One of the most unnatural changes we are experiencing, by safety concerns and government mandate, are the usual pleasantries and common courtesy of engaging with our Bahamian neighbors. Bahamians are generally warm and friendly people, and having to avoid contact with them is especially hard. I feel a sense of responsibility to be a good ambassador for my home country, the USA, whenever I travel and that usually includes meeting and embracing locals. Losing that opportunity has affected me more than I anticipated, and I expect people ashore that can’t visit friends or help out their neighbors can relate. Along a similar vein, while fatalities associated with any disease are tragic, Covid-19 patients passing away alone in a hospital, cutoff from loved ones, is truly horrifying. The importance of interpersonal relationships in living a meaningful life, whether strangers on an adventure or your closest kin, cannot be overstated.

While it is essential to be respectful of our host country’s regulations, there are situations that require us to fill in the blanks and read between the lines. Upon arriving into another foreign country via private sailboat, you generally deal with customs and immigration, which look at the vessel and her contents, and the people aboard, respectively. In our case, the vessel was cleared for three months, but due to the pandemic we were given the unusual clearance for only one month on our passports. So, during this time of isolation and lockdown, do we risk moving to renew? Is this essential travel? There is no clear instruction. We are forced to read between the lines, weigh risks, and interpret directives.

One of the most unnatural changes we are experiencing, by safety concerns and government mandate, are the usual pleasantries and common courtesy of engaging with our Bahamian neighbors. Bahamians are generally warm and friendly people, and having to avoid contact with them is especially hard. I feel a sense of responsibility to be a good ambassador for my home country, the USA, whenever I travel and that usually includes meeting and embracing locals. Losing that opportunity has affected me more than I anticipated, and I expect people ashore that can’t visit friends or help out their neighbors can relate. Along a similar vein, while fatalities associated with any disease are tragic, Covid-19 patients passing away alone in a hospital, cutoff from loved ones, is truly horrifying. The importance of interpersonal relationships in living a meaningful life, whether strangers on an adventure or your closest kin, cannot be overstated.

While it is essential to be respectful of our host country’s regulations, there are situations that require us to fill in the blanks and read between the lines. Upon arriving into another foreign country via private sailboat, you generally deal with customs and immigration, which look at the vessel and her contents, and the people aboard, respectively. In our case, the vessel was cleared for three months, but due to the pandemic we were given the unusual clearance for only one month on our passports. So, during this time of isolation and lockdown, do we risk moving to renew? Is this essential travel? There is no clear instruction. We are forced to read between the lines, weigh risks, and interpret directives.

Anchored in the lee of an island in the Bahamas.

As we attempt to refine priorities and devise a plan forward, days pass strangely. We stay busy with maintenance work that keeps the boat functioning, work online (Stephanie is employed remotely as an environmental consultant), find creative ways to acquire food, and try to appreciate the beautiful natural world that surrounds us. While this may sound idyllic to some, especially given how many people are cutoff from open space, the overall state of the world and uncertainty of our future tapers the enjoyment. Enter the emotional struggle.

Stephanie working hard to find more protein for our diets.

As we attempt to refine priorities and devise a plan forward, days pass strangely. We stay busy with maintenance work that keeps the boat functioning, work online (Stephanie is employed remotely as an environmental consultant), find creative ways to acquire food, and try to appreciate the beautiful natural world that surrounds us. While this may sound idyllic to some, especially given how many people are cutoff from open space, the overall state of the world and uncertainty of our future tapers the enjoyment. Enter the emotional struggle.

Stephanie working hard to find more protein for our diets.

Living on a boat is a precarious balance between discomfort and rewarding experiences. We give up many comforts to live the way we do, but ordinarily gain such incredible experiences by successfully planning voyages to new locations, that the juice is worth the squeeze. But sometimes that balance is…well, um, imbalanced, and we seek breaks to our routine, as does anyone I’m sure.

To accomplish this, Stephanie and I have a safe word. Technically it is a safe sentence and it is not very cryptic. Actually it is quite literal. “I want to get off of the boat”. We live in a confined space and sometimes that space is quite uncomfortable. Sometimes it rocks or rolls, bounces, or is hot and humid, or leaks either salt water or rain water. Sometimes the misery is short lived. Sometimes it feels like it will be endless. If either of us say this line, we both have to work expeditiously to move somewhere where there is a beach to walk, a road to jog, or a hotel to check into (depending on the frustration level). That’s the deal we have with one another. We knew that we would occasionally need to take a break from the boat and seek some space and comforts. However, that sentence was created pre-pandemic. Now there are no hotels to check into and the road that leads to town should be avoided. Our backup plan is off limits for now and that just adds a little bit more stress to the situation. If we need a break, we can’t take it, and I imagine couples around the planet are in a similar *cough* boat.

Living on a boat is a precarious balance between discomfort and rewarding experiences. We give up many comforts to live the way we do, but ordinarily gain such incredible experiences by successfully planning voyages to new locations, that the juice is worth the squeeze. But sometimes that balance is…well, um, imbalanced, and we seek breaks to our routine, as does anyone I’m sure.

To accomplish this, Stephanie and I have a safe word. Technically it is a safe sentence and it is not very cryptic. Actually it is quite literal. “I want to get off of the boat”. We live in a confined space and sometimes that space is quite uncomfortable. Sometimes it rocks or rolls, bounces, or is hot and humid, or leaks either salt water or rain water. Sometimes the misery is short lived. Sometimes it feels like it will be endless. If either of us say this line, we both have to work expeditiously to move somewhere where there is a beach to walk, a road to jog, or a hotel to check into (depending on the frustration level). That’s the deal we have with one another. We knew that we would occasionally need to take a break from the boat and seek some space and comforts. However, that sentence was created pre-pandemic. Now there are no hotels to check into and the road that leads to town should be avoided. Our backup plan is off limits for now and that just adds a little bit more stress to the situation. If we need a break, we can’t take it, and I imagine couples around the planet are in a similar *cough* boat.

Stephanie digging deep into the vertical freezer to locate some food.

Life ashore, while more comfortable, is fundamentally similar. Working hard in ones career to make ends meet is balanced by weekend adventures, quality time with loved ones, and the freedom to roam when restless. We need those rewards, both aboard and ashore, to help us push through the hardships. Living through this pandemic is especially challenging because it increases the discomforts and diminishes the rewards. Add to that the fear of the unknown: the general discomfort of living through an evolving crisis with an uncertain future and small rewards become even more essential.

Life ashore, while more comfortable, is fundamentally similar. Working hard in ones career to make ends meet is balanced by weekend adventures, quality time with loved ones, and the freedom to roam when restless. We need those rewards, both aboard and ashore, to help us push through the hardships. Living through this pandemic is especially challenging because it increases the discomforts and diminishes the rewards. Add to that the fear of the unknown: the general discomfort of living through an evolving crisis with an uncertain future and small rewards become even more essential.

Keeping busy by experimenting with sailing rigs for an inflatable paddleboard using mostly beach-supplied parts and, of course, zipties.

Sometimes in a moment of weakness I let frustration get to me and I get frustrated with the boat and get frustrated with living here and frustrated with my small, hot, rolly, space. But I have to check myself and remind myself that I’m alive and people are dying. Can I be this blind? I am getting frustrated cooking food while there are many people who can’t afford food? I’m annoyed. I’m annoyed at myself that I am feeling annoyed! People are dying, alone, in hospitals, so my feeling of annoyance simultaneously feels totally unfair and selfish. I am frustrated that it is hot and my home is rolly, meanwhile people are loosing their homes. This makes me feel worse. How can I feel more grateful? I need a reset.

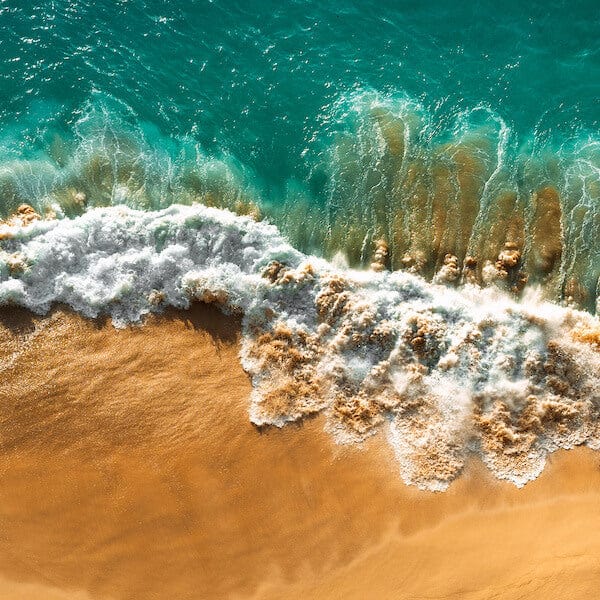

I want to do something but everything feels like effort. I want to appreciate the beautiful surroundings but it is the same view I have had for a month. The same white sand beach, gin clear water and seemingly endless bright sun. It has become normalized. I hate that. Some people aren’t even allowed to leave their apartment and I’m bored of my Caribbean paradise? I get mad at myself. A year from now I wont have these views and I will regret not appreciating them more. I get frustrated by my complacency with the natural beauty. “Dang it Conor, you should be more in awe of this beautiful water!”

These frustrations put me on edge and make it harder to interact with my significant other because I am wound up and peevish. She is similarly frustrated and when we interact I struggle to maintain our (usually) courteous discourse. My inflections change. My usual elaboration of a topic gets curtailed more quickly. When we are on the edge of ear-shot and we can’t quite hear each other, I want to take the (superficially) easy-way out and just say “nevermind”. It is easier for me to just mutter a “forget it” under my breath than moving closer, re-organizing my words and trying again with an un-eroded tone. But that is what I have to do. She needs me to be strong.

Sometimes in a moment of weakness I let frustration get to me and I get frustrated with the boat and get frustrated with living here and frustrated with my small, hot, rolly, space. But I have to check myself and remind myself that I’m alive and people are dying. Can I be this blind? I am getting frustrated cooking food while there are many people who can’t afford food? I’m annoyed. I’m annoyed at myself that I am feeling annoyed! People are dying, alone, in hospitals, so my feeling of annoyance simultaneously feels totally unfair and selfish. I am frustrated that it is hot and my home is rolly, meanwhile people are loosing their homes. This makes me feel worse. How can I feel more grateful? I need a reset.

I want to do something but everything feels like effort. I want to appreciate the beautiful surroundings but it is the same view I have had for a month. The same white sand beach, gin clear water and seemingly endless bright sun. It has become normalized. I hate that. Some people aren’t even allowed to leave their apartment and I’m bored of my Caribbean paradise? I get mad at myself. A year from now I wont have these views and I will regret not appreciating them more. I get frustrated by my complacency with the natural beauty. “Dang it Conor, you should be more in awe of this beautiful water!”

These frustrations put me on edge and make it harder to interact with my significant other because I am wound up and peevish. She is similarly frustrated and when we interact I struggle to maintain our (usually) courteous discourse. My inflections change. My usual elaboration of a topic gets curtailed more quickly. When we are on the edge of ear-shot and we can’t quite hear each other, I want to take the (superficially) easy-way out and just say “nevermind”. It is easier for me to just mutter a “forget it” under my breath than moving closer, re-organizing my words and trying again with an un-eroded tone. But that is what I have to do. She needs me to be strong.

A pre-pandemic, non-stressful day enjoying a waterfall. It is easy to communicate with your partner when everyone is having fun exploring.

Seamanship is often defined as “doing what you know is right, at the moments you want to do it least.” I often interpreted this as investigating the funny noise at 2 am in the rain or forgoing a beach party to climb the mast to inspect critical connections before a passage. But this pandemic is teaching me that this description is applicable to sailors and non-sailors, alike.

I am accustomed to pushing myself mentally and physically while offshore sailing. Life at sea demands attention, energy and focus and I have to constantly push myself physically to attend to the ever-present boat chores, to navigate, to trim sails and cook and clean. Now that some of my ambitions to visit other countries, requiring a thousand offshore miles of sailing, are curtailed for now, I have excess time and energy that can be refocused to my significant other. I no longer worry about passing ships in the night, or reducing sails in rain squalls, I have a relationship that is affected by the global pandemic that requires my attention.

I am learning that I need to re-channel my energy to properly communicate, especially when I want to least, which is when I am tired, frustrated by the boat and irritated at some inconsequential thing. It is easy to be short or snarky and vent my frustration to Stephanie unwittingly. Daily annoyances can easily permeate into other aspects of our lives.

Therefore I am pushing myself to filter out frustrations before passing them onto Stephanie and to communicate fully and wholeheartedly. To be supportive of Stephanie’s daily goals and desires, no matter how big or small: to be her champion. I am realizing that I can’t control many aspects of our life right now, but I can control my reaction to those events and I can work on being a better partner. In the end, any efforts I put forth come back ten fold, so the investment is always wise. I suspect this lesson will serve me well in marriage.

Stephanie and I getting engaged in Jamaica, just prior to the Coronavirus pandemic.

You might be asking yourself, where are we going from here? We ask ourselves that everyday. These remote islands are far from health care, and our Coronavirus risk-assessment is that of small risk but large consequences. We are unlikely to contract the virus. We are unlikely to spread it. But if we did contract the virus, the consequences are huge. We are a 72-hour sail to Florida. If we try to arrange commercial travel, we endanger those who we encounter during transport. We must remain diligent and safe and we believe that means we must remain isolated and protected.

Therefore, we decided it is best to stay put and not move inter-island to renew our visas. I think it is safest for the Bahamas, and for us, to remain isolated and if the ramifications upon our eventual renewal are that we are forced to leave the country, well at least our conscience is clear and our hearts were in the right place.

I hope everyone continues to make the best of their situations, whatever they may be. Be safe, count your blessings, communicate thoughtfully and support a loved one. Learn from the lessons of the sea. Be a good seaman: Do what you know is right, in the moments you want to do it least. And remember, love is effort and happiness is a decision.

Signing off, somewhere in the lee of an island, in 7’of water, on the edge of cell service.

Seamanship is often defined as “doing what you know is right, at the moments you want to do it least.” I often interpreted this as investigating the funny noise at 2 am in the rain or forgoing a beach party to climb the mast to inspect critical connections before a passage. But this pandemic is teaching me that this description is applicable to sailors and non-sailors, alike.

I am accustomed to pushing myself mentally and physically while offshore sailing. Life at sea demands attention, energy and focus and I have to constantly push myself physically to attend to the ever-present boat chores, to navigate, to trim sails and cook and clean. Now that some of my ambitions to visit other countries, requiring a thousand offshore miles of sailing, are curtailed for now, I have excess time and energy that can be refocused to my significant other. I no longer worry about passing ships in the night, or reducing sails in rain squalls, I have a relationship that is affected by the global pandemic that requires my attention.

I am learning that I need to re-channel my energy to properly communicate, especially when I want to least, which is when I am tired, frustrated by the boat and irritated at some inconsequential thing. It is easy to be short or snarky and vent my frustration to Stephanie unwittingly. Daily annoyances can easily permeate into other aspects of our lives.

Therefore I am pushing myself to filter out frustrations before passing them onto Stephanie and to communicate fully and wholeheartedly. To be supportive of Stephanie’s daily goals and desires, no matter how big or small: to be her champion. I am realizing that I can’t control many aspects of our life right now, but I can control my reaction to those events and I can work on being a better partner. In the end, any efforts I put forth come back ten fold, so the investment is always wise. I suspect this lesson will serve me well in marriage.

Stephanie and I getting engaged in Jamaica, just prior to the Coronavirus pandemic.

You might be asking yourself, where are we going from here? We ask ourselves that everyday. These remote islands are far from health care, and our Coronavirus risk-assessment is that of small risk but large consequences. We are unlikely to contract the virus. We are unlikely to spread it. But if we did contract the virus, the consequences are huge. We are a 72-hour sail to Florida. If we try to arrange commercial travel, we endanger those who we encounter during transport. We must remain diligent and safe and we believe that means we must remain isolated and protected.

Therefore, we decided it is best to stay put and not move inter-island to renew our visas. I think it is safest for the Bahamas, and for us, to remain isolated and if the ramifications upon our eventual renewal are that we are forced to leave the country, well at least our conscience is clear and our hearts were in the right place.

I hope everyone continues to make the best of their situations, whatever they may be. Be safe, count your blessings, communicate thoughtfully and support a loved one. Learn from the lessons of the sea. Be a good seaman: Do what you know is right, in the moments you want to do it least. And remember, love is effort and happiness is a decision.

Signing off, somewhere in the lee of an island, in 7’of water, on the edge of cell service.

Dr. Conor Smith is a marine scientist who is widely considered by his peers as the modern version of Macgyver. An avid sailor and science communicator, he blends his passion for the ocean with his background in marine physics. You can read his dissertation here and follow his and Stephanie's sailing adventures on Instagram @dinghyride.

Matt Archer

February 12, 2026

I only just found this, Conor! It was a joy to read. Your writing is gin clear (love it :D), and it was interesting to learn more about your experience onboard Grace during COVID. I love the big photos throughout, my heart yearns for another Bahamas sailing trip!