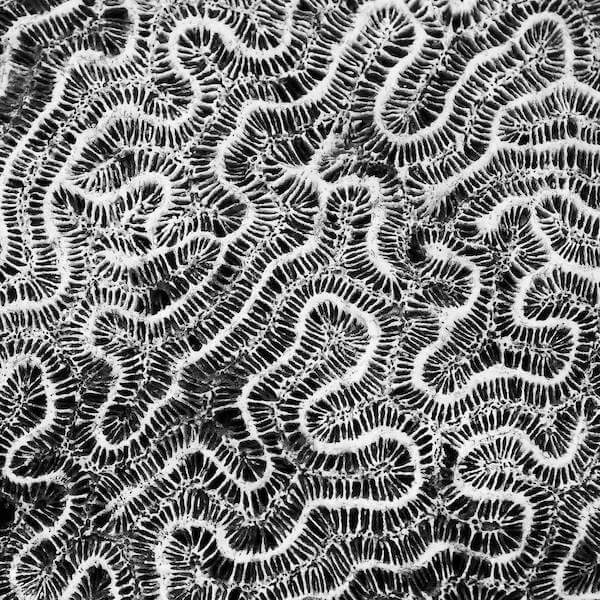

Do you know how much live coral we have on the Great Barrier Reef? What about in the Red Sea, Indonesia, or the Belize Barrier Reef? No? Well, that’s not surprising because scientists can’t tell you the answer to that either. That might sound crazy, but we don’t know these answers for very good reasons. To understand these reasons, the implications of not knowing, and what we’re doing to learn more, read on!

Why is it so hard to know how much coral we have?

As an Earth observation scientist, I consider myself somewhat of a biographer for Mother Earth. I tell stories of her ecosystems and how they change over time. And I use satellites and drones as my scientific illustrators. One of the stories that I’ve focused on since the late 1990’s, is about live coral on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR).

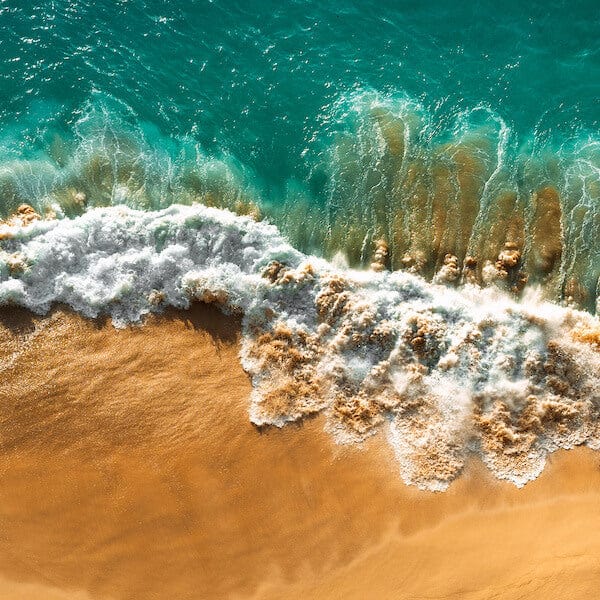

We certainly know a lot about the GBR from decades of scientific research. But why don’t we know how much live coral there is? To understand the answer to that question, we need to consider just how big the GBR is. It’s the size of the Australian states Victoria and Tasmania combined. Or about the size of Japan, Malaysia, or Italy. Or half the size of Texas. So, it’s a really big area! What’s more, most of it is extremely remote and can take many days at sea to access. With this in mind, it’s actually not that surprising that we don’t know exactly what’s out there.

But why is that a problem?

Fundamentally, if we don’t understand what we have, we cannot be certain if we are losing it. And if so, by how much.

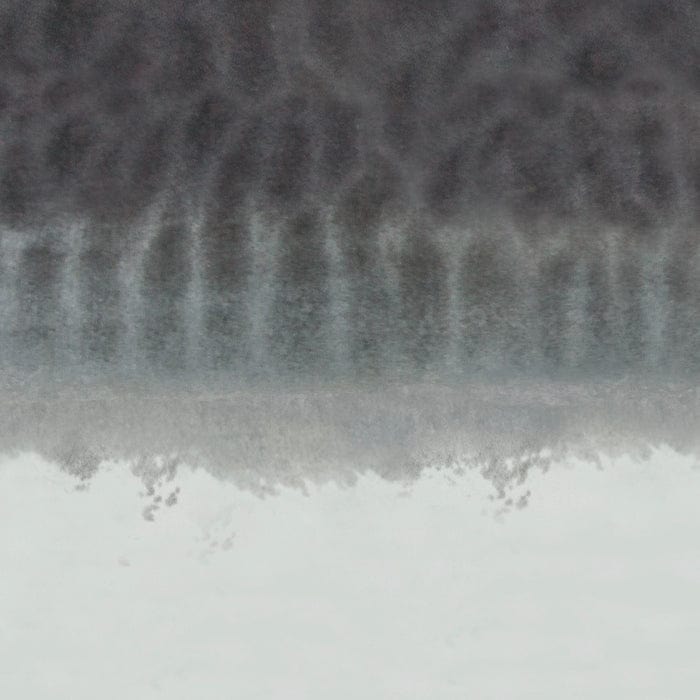

How much living coral is down there? Satellite image of the Great Barrier Reef. Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC

The problem with not knowing

In 2016, there was huge media hype about the extent of coral bleaching on the GBR. Some outlets mistakenly reported that 95% of the GBR was bleached. Or that 95% of corals on the GBR were bleached. However, the actual statement was that 95% of reefs on the GBR experienced some bleaching. While these statements are all devastating, the slight word switches have massive implications on their meanings.

We simply do not have the data or the means to assess the level of bleaching at the coral scale across the whole GBR. Just as we don’t know how much live coral was there in the first place, or how this has changed after a bleaching event and in periods of recovery.

As scientists, we predict, estimate, and generalize based on the available data. So, let’s take a look at what we do know, and how Earth observation tools help us.

Often the safest way to retrieve a drone on a boat is to catch it! Photo Credit: Harriet Spark, Grumpy Turtle Creative

How Earth observation helps us understand our planet

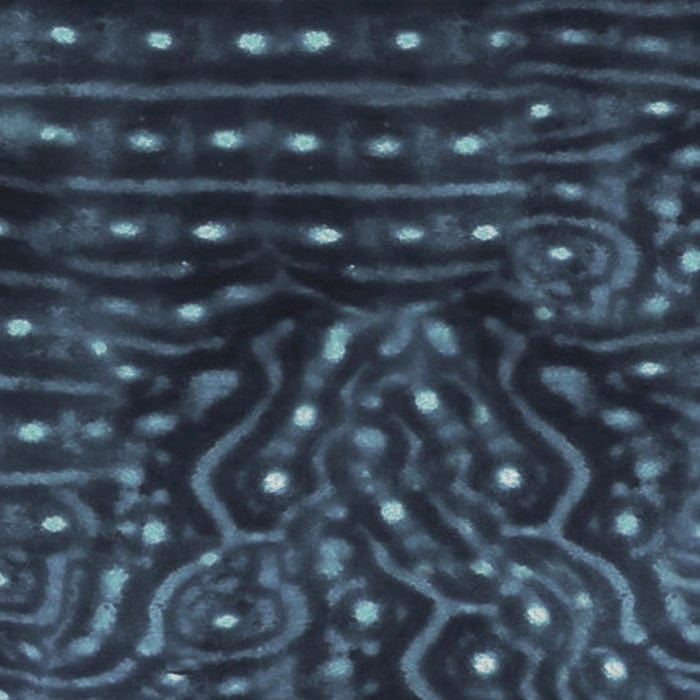

If you’ve ever explored Google Earth, you’ve experienced what Earth observation satellites have to offer. From several hundred kilometers away, these satellites do a fantastic job capturing imagery of global coral reefs. They help us understand where the reefs are, how many we have, and some basic geomorphic information (shape and structure).

But as fabulous as satellites are for broad scale coverage, they lack fine scale detail. This means that we can’t use them to identify the difference between individual features on the reef such as coral, algae, and seagrass. It is sometimes possible to identify areas of mass coral bleaching, where the change covers large continuous patches of reef. But only if the satellite manages to capture data at just the right time, and when it’s not cloudy. It’s not always easy to align the perfect conditions!

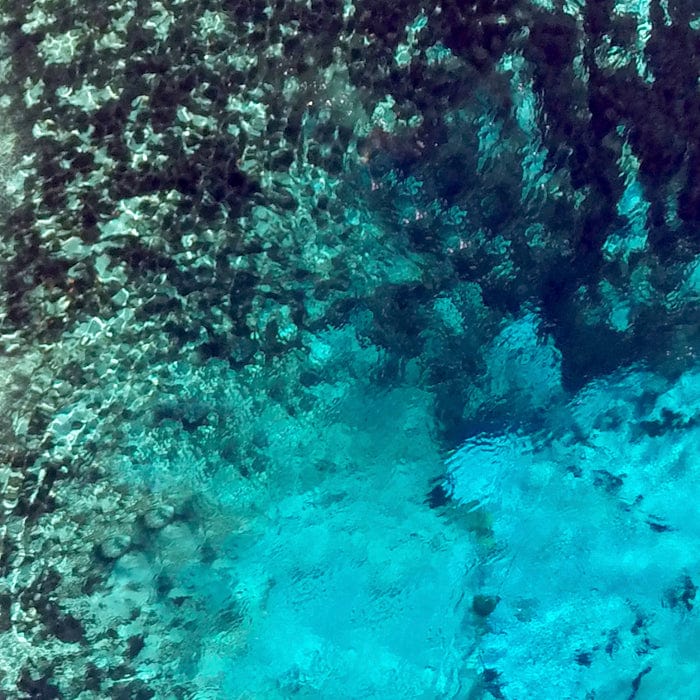

The best way to be certain about the existence and location of live coral is to put our faces in the water. In this way, scientists (including citizen scientists) have been learning about coral reefs worldwide for decades. But there’s only so far we can swim, and so we are limited in coverage and still can’t answer the question – how much live coral is on the GBR?

This is where drones can provide an excellent middle ground (or sky?!) between the fieldwork we do, and the detail that the satellite images provide.

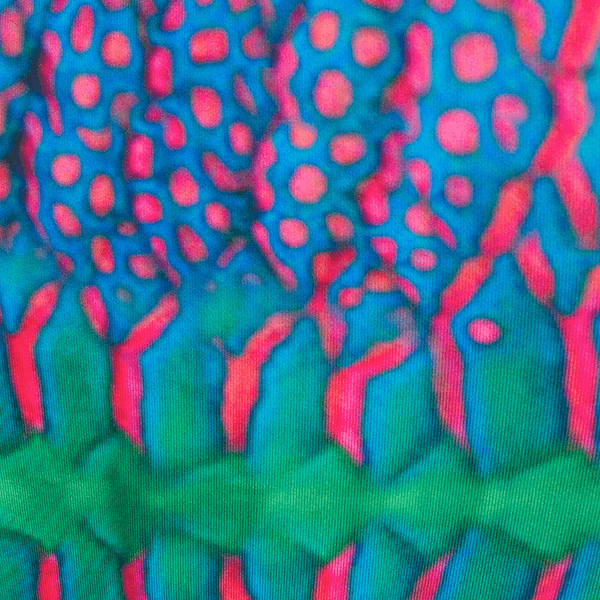

Drone image of a coral reef.

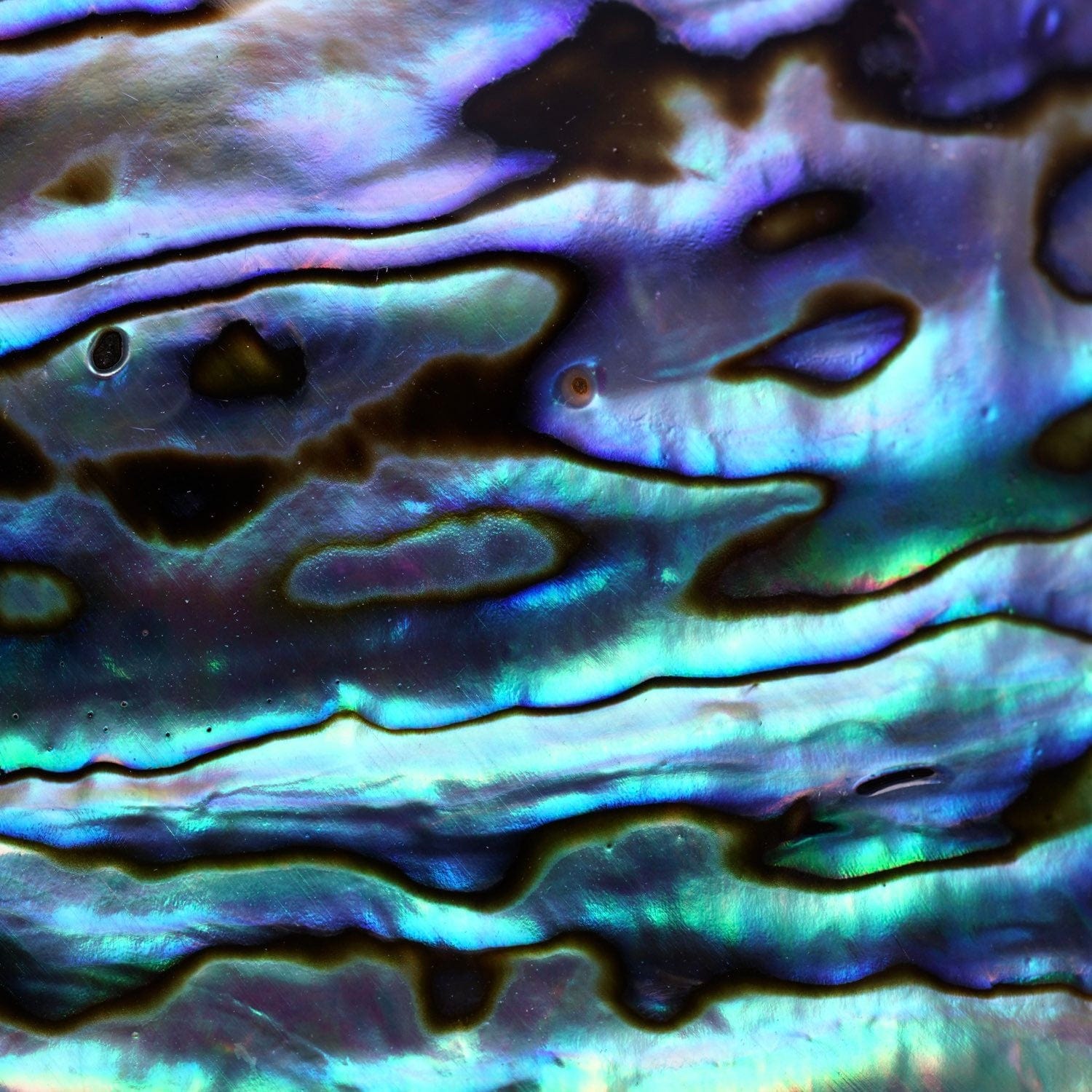

Coral reef drone mapping is special

I started using drones for coral reef mapping in 2016. I am still mind blown by the quality of data that we can capture with this increasingly pocket-sized technology! I love the level of detail I can see on the reef, from a perspective that’s different to what we see when we are underwater. It’s also super handy to be able to capture data at the ‘Goldilocks hour’ - when the time is ‘just right’. That means waiting for the best sun angle, at low tide, when the breeze drops. That’s when the magic happens.

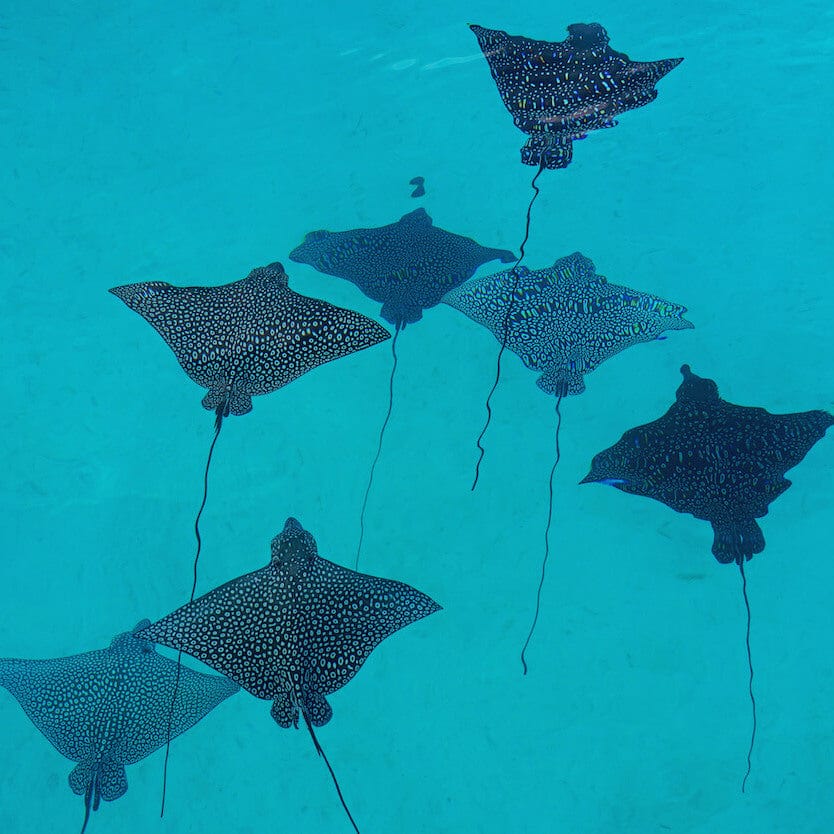

When the conditions are just right, not only can we see and map the live coral, but we can see lots of other different types of critters on the reef as well. One of my favourite projects has been to estimate the amount of poo contributed to the reef by sea cucumbers! What comes out of a sea cucumber is surprisingly cleaner than what goes in. So, their poo is of great service to the reef. I realised that we could use drones to count sea cucumbers and we combined this information with the ‘poo rate’ of an individual to estimate the amount of poo per year on the reef.

While this might sound a little crazy and academic, it has led our team to a much larger project using aerial and underwater drones to monitor sea cucumbers throughout the GBR. The drones help us take stock of this important beche de mer fishery. All the while I’m also mapping their habitat and continuing to work towards learning how much live coral we have.

(Top) When I'm not mapping with my drone, I'm mapping underwater with three GoPros and a GPS Photo Credit: Harriet Spark, Grumpy Turtle Creative (Bottom) Results from underwater mapping - so much detail!

Why I’m lucky to be involved with drone mapping

I feel hugely privileged to spend time at research stations and on different vessels in pursuit of my mapping questions. To wake up to sunrise on the reef in a remote location where I can see the horizon in every direction I look reminds me to take a deep breath, pause, do a little yoga, and feel endless gratitude for these experiences. After the moment of peace, the hard work begins.

Because as exotic as the location may be, our work is expensive, so we must make the most of every single second. When we’re not flying, we are constantly planning missions, charging batteries, checking and processing data. And when the tide isn’t ideal for flying, we’re in the water snorkeling to check that what we are seeing from the air is what we know it to be from underwater. Oh, and eating! I use up so much nervous energy that only subsides when the drone is safely on deck and the data have passed our quality check.

My drone mapping missions have taken me up and down the GBR and to parts of the Belize Barrier Reef as well. But I could spend my entire life capturing data and still not make a dent in covering these vast areas. As I started to consider how small I am with both the challenge and opportunity to map the world’s coral reefs, I’ve turned to other scientists and citizen scientists to help.

Processing imagery from a day's survey. Photo Credit: Harriet Spark, Grumpy Turtle Creative

Can we have a collective drone mapping impact?

There are hundreds of thousands of drones in circulation around the world. What if everyone who had access to a drone used it to capture valuable information about their local land and sea country? What if we all worked together to make the most detailed map of Earth to save at-risk ecosystems?

Making this a reality is now the focus of my work as an Earth observation scientist and biographer of Mother Earth. If you have a drone and would like to contribute, I would love to hear from you! I’ve already begun curating data from all over the world and have imagery from 63 countries – you can see it all here. There’s close to one million drone mapping images available. So even if you don’t fly a drone, you can still view the data of others and travel vicariously throughout the Great Barrier Reef, Belize, Maldives, New Caledonia, Japan, French Polynesia, and Indonesia.

If you’d like to learn more about drone mapping and how to get involved, here’s a link to my free e-book.

Already have a drone and would like to contribute? Or otherwise access drone data from around the world? Head to www.geonadir.com to learn more.

Associate Professor Karen Joyce is the Co-Founder and Technical Lead of GeoNadir and an academic at James Cook University in Cairns, Australia. She is a multi-award winning geospatial scientist, working for more than 20 years in government, industry, the military, and academia. She has been involved in tertiary education since the late ’90’s, and online education for the past 12 years. Her online resources are accessed nearly 30,000 times every month and she is constantly creating content as technology changes. Karen is a qualified remote pilot and has been flying drones of all sizes with a variety of sensor payloads since 2013, with most of her research conducted on the Great Barrier Reef.

Photo credit: header image by Chris Roelfsema

Reshma desai

August 27, 2023

How can I get involved in the data part of it. I’m in Chicago but want to help! Thanks