Join me, Dr. Carl Polypson, a coral who lives off the coast of Florida, on a fascinating journey through my complex life cycle. Despite forming the largest living structures on Earth, me and my coral brethren all started as tiny, microscopic organisms, just drifting along in the vast ocean, barely noticeable to the naked eye. But don't just take my word for it, let me take you on an adventure through my incredible story.

My life probably began a little different than yours. There’s this special night, usually once a year, when all the parent colonies on a reef release their eggs and sperm into the water simultaneously. We call it mass spawning. It’s critical they all release their gametes – eggs and sperm – at the time, so they can mingle with those of other corals to create offspring with lots of genetic diversity.

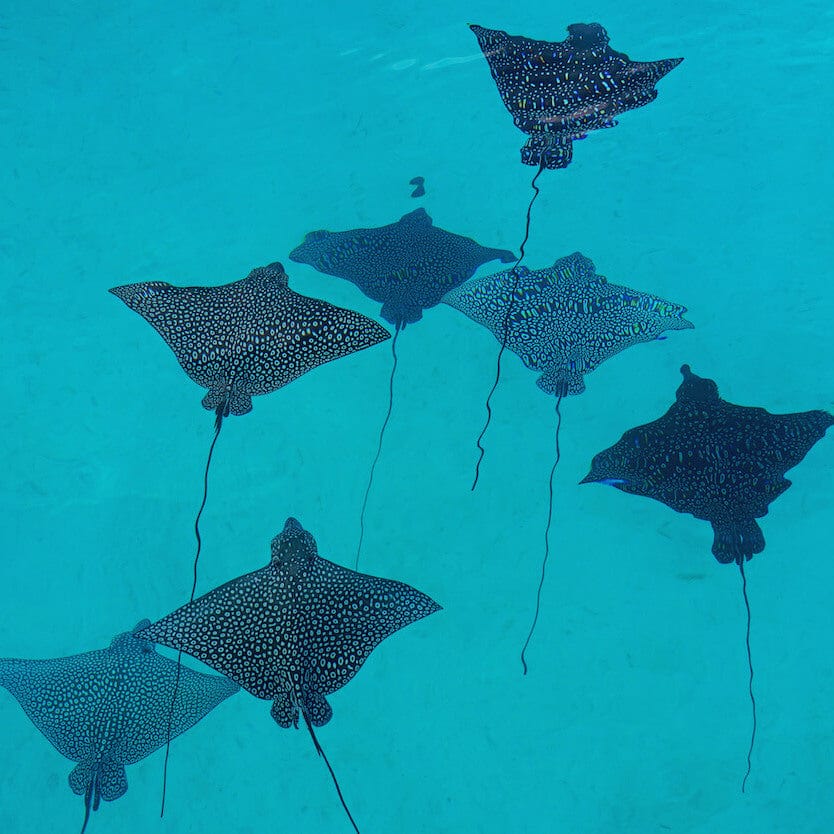

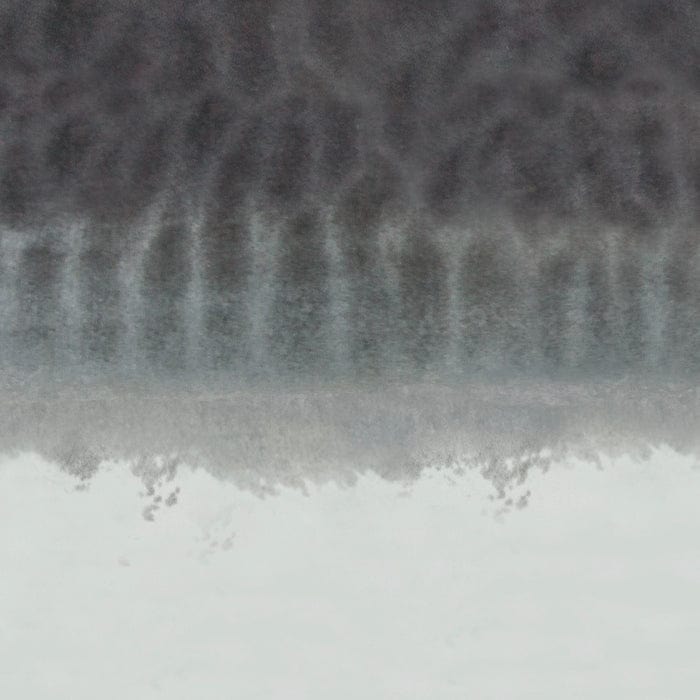

Elkhorn corals are an iconic coral species, creating complex three-dimensional habitat on reefs throughout Florida and the Caribbean

My parents detected cues from the environment, including water temperature, day length, and moonlight, to determine when to spawn. Rising water temperatures through the spring and early summer trigger “gametogenesis”, when adult corals produce eggs and sperm and get them ready for spawning. To pinpoint the specific day to spawn, they use photoreceptors to detect moonlight – most corals spawn a few days after the full moon, when the light they detect begins to wane in intensity. They also use these photoreceptors to determine the time of day - most typically spawn just after sunset. When the time is right, parent colonies send chemical messages to one another through the water, signaling that they’re ready to spawn.

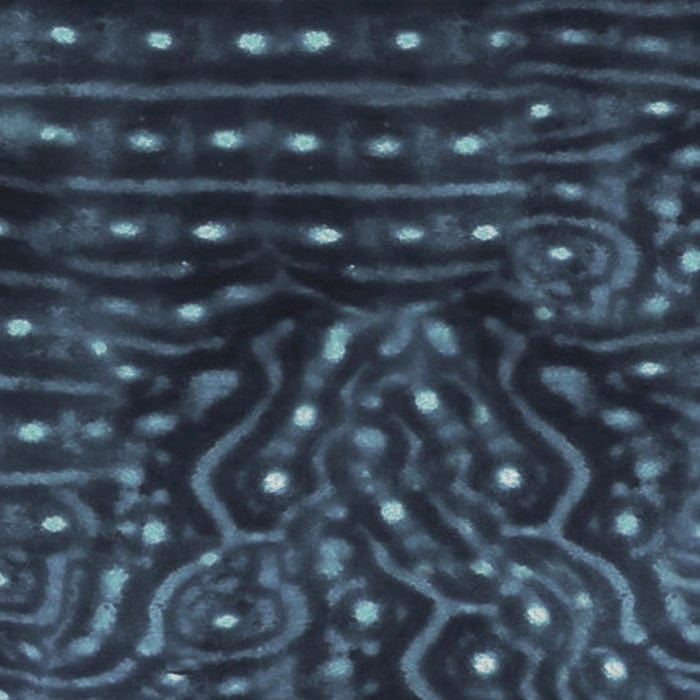

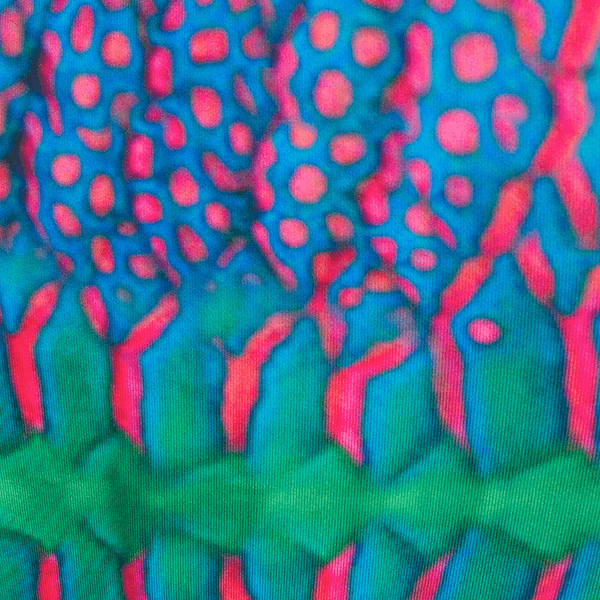

Right on cue, my parents and all the other corals on the reef released their gametes into the dark water. There were hundreds of thousands of little pink balls of eggs and sperm, making the reefscape look like an underwater snowglobe.

Elkhorn corals release bundles of eggs and sperm off the coast of Key Largo, Florida. These corals spawn just a few nights each year.

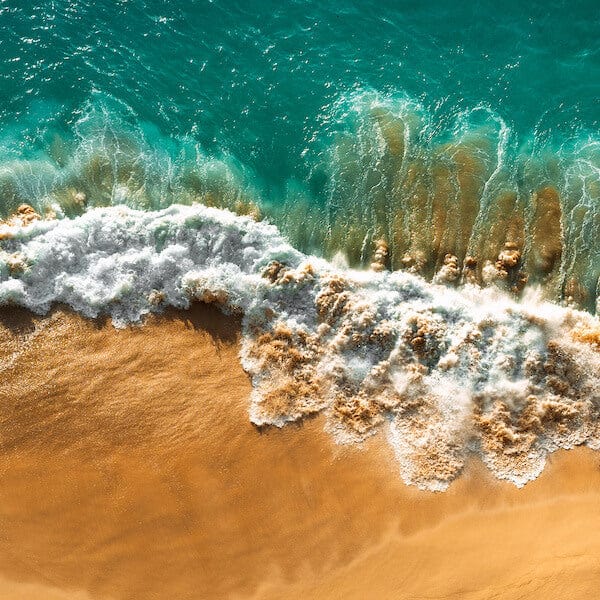

The gametes are positively buoyant, because they are packed with lipids, or fats, which will help nourish the resulting offspring. They slowly drift to the surface of the ocean, where they mix and fertilize, forming ME and millions of other tiny embryos. Soon, we began cell division, going from one cell to two to four, and so on. By the end of the night, I changed from a single-celled embryo into a multicellular larva. Together, my siblings and I became the foundation of tomorrow’s reef!

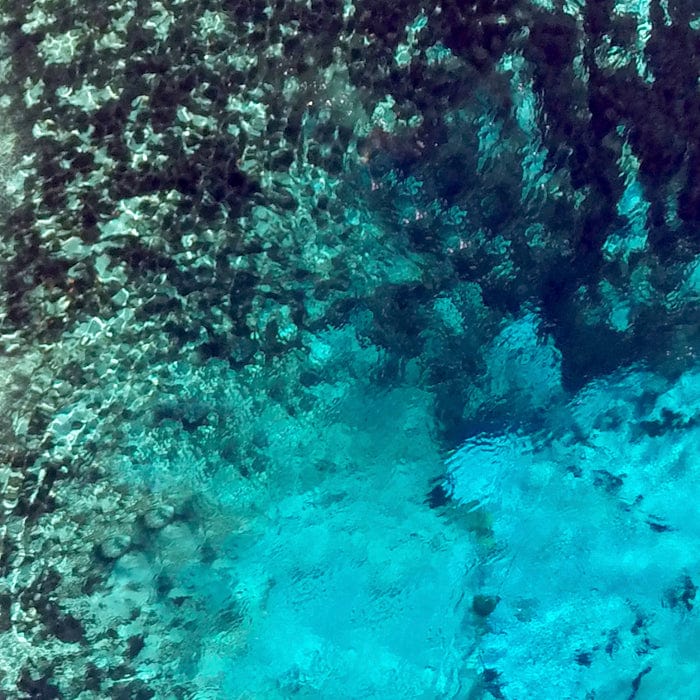

Positively-buoyant coral gametes fertilize one another in the darkness of the sea, creating embryos that will be carried by the ocean currents for days or weeks before finding a place to settle.

As a coral larva, I spent the first several days of my life drifting along with the ocean currents, completely at the mercy of the environment around me. I looked more like an amoeba than a coral, just an oval-shaped ball of cells dividing and dividing. I had no means of getting around, relying solely on the current to carry me. It was kinda scary as I could have ended up far away from my birthplace.

During this time, I was extremely vulnerable to predation and other environmental factors, such as temperature and salinity changes. I hadn't started hosting algal symbionts or grown any tentacles to feed with, so I relied on the fat reserves from my natal yolk sack – which also made me a tasty, nutritious snack for plankton-feeding animals like fish! Because of these threats, many of my siblings and cousins did not survive the larval stage, and only a small percentage of us eventually settled on the ocean floor.

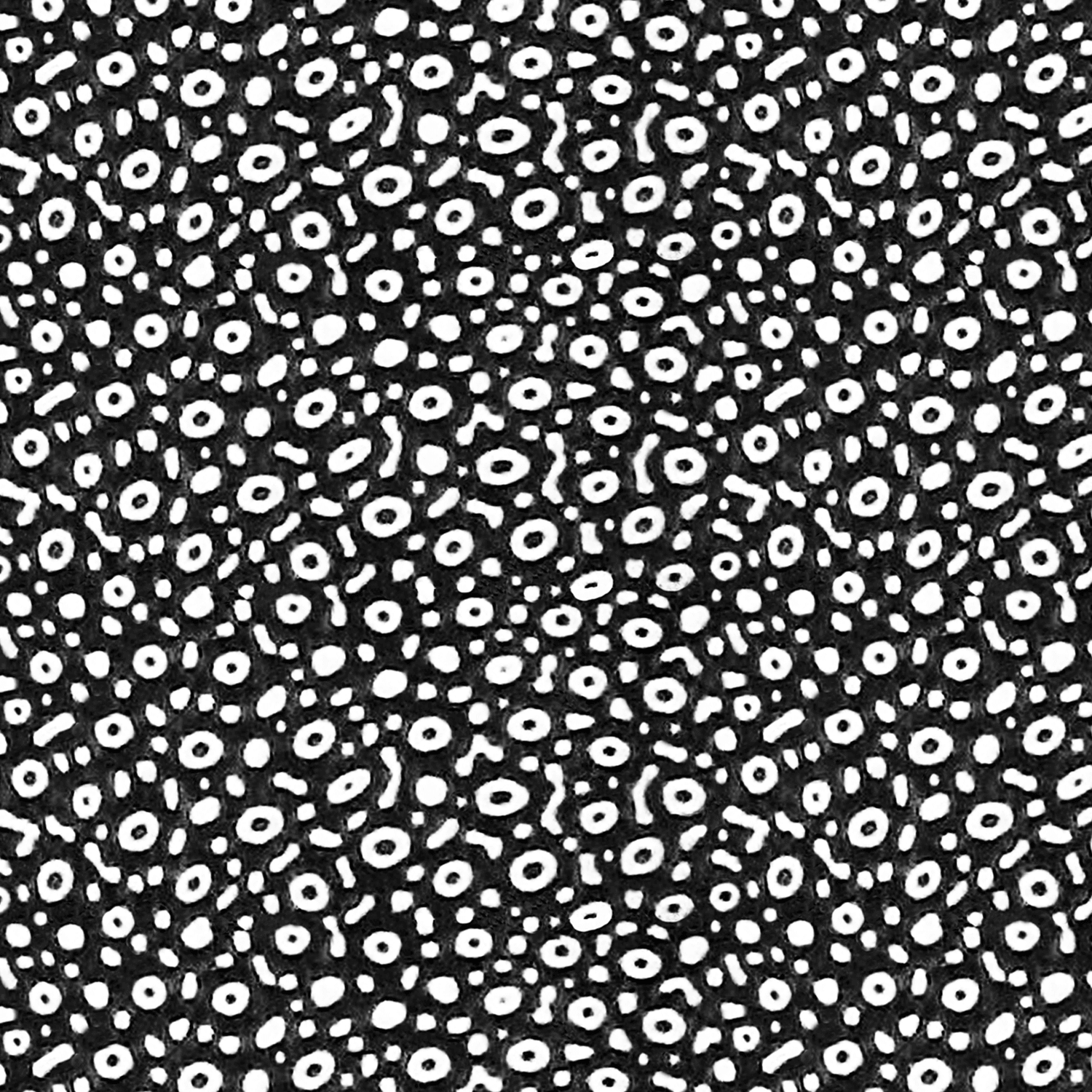

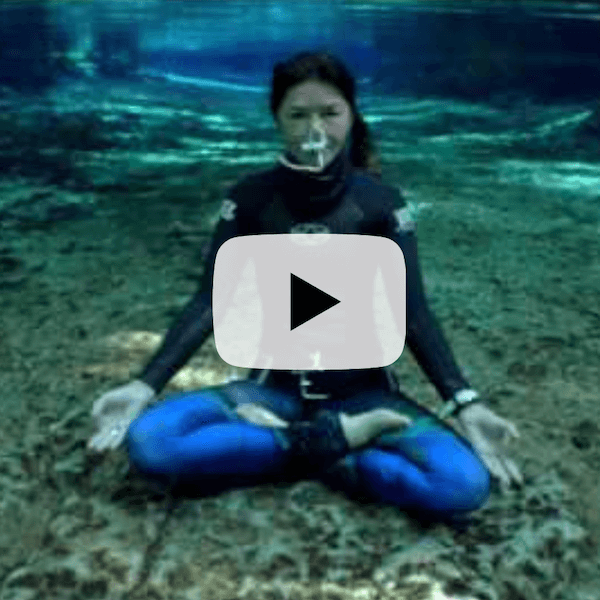

Coral larvae develop tiny cilia, or hairs, which help them swim towards the ocean floor and select a suitable place to attach themselves.

After a little while, I began to gain a bit more agency – I developed tiny hairs, called cilia, along my body, which beat to help me swim through the water. I could only swim weakly, and still couldn't overcome major currents, but I was able to bring myself toward the ocean floor and search around for a place to attach myself permanently, or settle. I choose optimal habitat by using chemical cues to sense the presence of important reef species like other corals and algae.

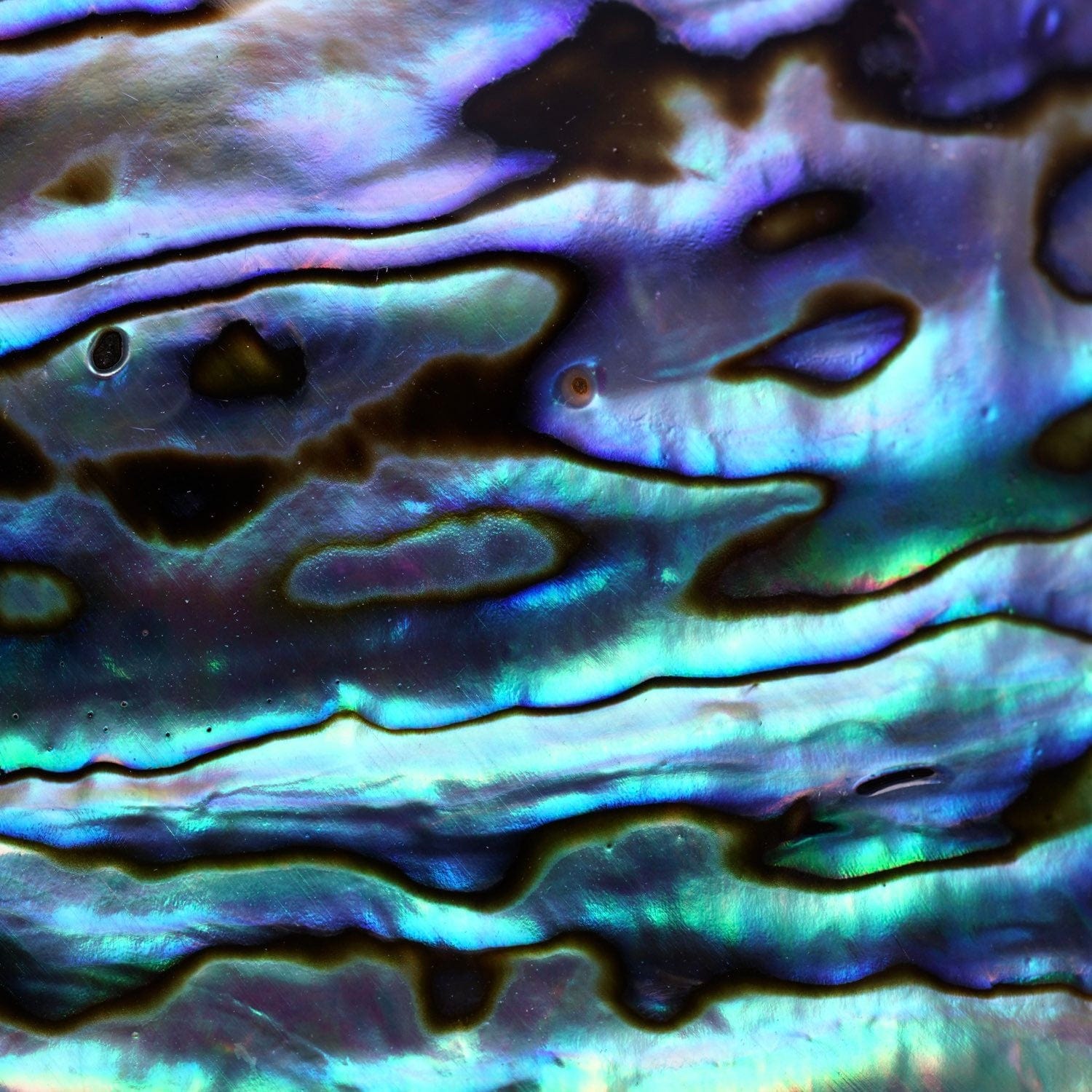

Once I found a suitable place to call home, I attached myself to a hard surface, such as a rock or the remains of another coral, and began my metamorphosis. I secreted a calcium carbonate skeleton around myself for protection, just like my parents did when they were settling. I formed a mouth, followed by tentacles, which enable me to capture tiny particles from the water as food - no yolk sac needed anymore! By feeding, I also ingested algal symbionts, which I incorporated into my tissues as my first symbiotic partners. Throughout my life, I will rely on this symbiotic relationship I have with tiny photosynthetic algae. These algae live inside my tissue and provide me with vital nutrients and oxygen through photosynthesis. In return, I provide the algae with a safe place to live and access to the nutrients they need to thrive.

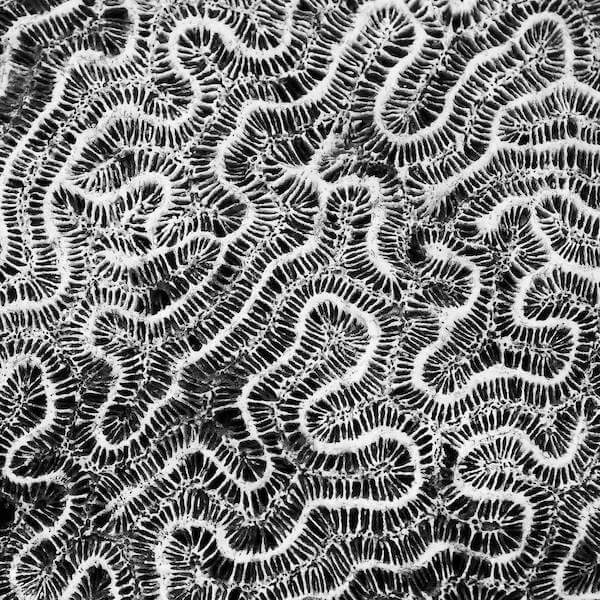

A "primary polyp", or recently-settled baby coral, develops a mouth and tentacles and begins to look more like an adult coral.

By this point I’m what is called a “primary polyp”, and for the first time I looked less like an amoeba and a little more like a coral. With my algal symbionts to help me photosynthesize and my tentacles to help me feed, I gathered enough energy to grow and divide asexually, creating new polyps that will form a colony with me as the foundation. This process can be pretty slow - though my growth can vary quite a bit depending on my species, location, and conditions, I may be no larger than a golf ball by the time I’m one year old, and no larger than a basketball by my fifth birthday.

A juvenile staghorn coral, just over one year old, grows its first branches and begins to establish itself as a new colony on the reef.

Because we stay small for so long, juvenile corals like me are vulnerable to predation and competition - many reef animals like fish or carnivorous snails might find me to be a tasty snack, and other, larger organisms like seaweeds may grow over and smother me. If I’m lucky, I’ll survive and grow, more and more. Each new polyp adds to my growing three-dimensional structure, and together we create a complex, interconnected system that provides shelter and habitat for a wide variety of marine life.

After about five to ten years, I finally reached sexual maturity, when I started to develop my own gametes and reproduce through spawning during our annual coral spawning events. And then the process starts all over again!

At just a few years old, young elkhorn coral colonies have grown numerous branches and contribute to building complex structure on the reef.

Just like it was for my parents all those years ago, it is important for me to release my gametes at the right time to increase the chances of fertilization and the survival of my offspring.

Overall, the completion of this complicated life cycle is critical for the health of coral reef ecosystems. Climate change, pollution, and overfishing are all major threats to our survival at all life stages, especially as larvae and juveniles, making it important for humans like YOU to take action to reduce your impacts on ocean life and protect us.

Dr. Carl Polypson lives off the coast of Miami on a tropical reef. He spends most of his time eating, hosting algae guests, reproducing, and contemplating his life. He majored in Coral Communications with a minor in Dance from the prestigous Whalewarts School. His dissertation, "How did I get here? - Stochastic Modeling of Coral Recruitement off the South Atlantic Bight" remains unpublished in the peer-reviewed literature, yet is praised as a significant literary accomplishment for a simple-celled Anthozoa.

Dr. Polypson collaborated with Dr. Liv Williamson on this article, and thanks her for her contributions.

Stella Fickling

April 29, 2023

What a brilliantly composed and delightful way of explaining and illustrating such a beautiful event!