“If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.”– Shirley Chisholm

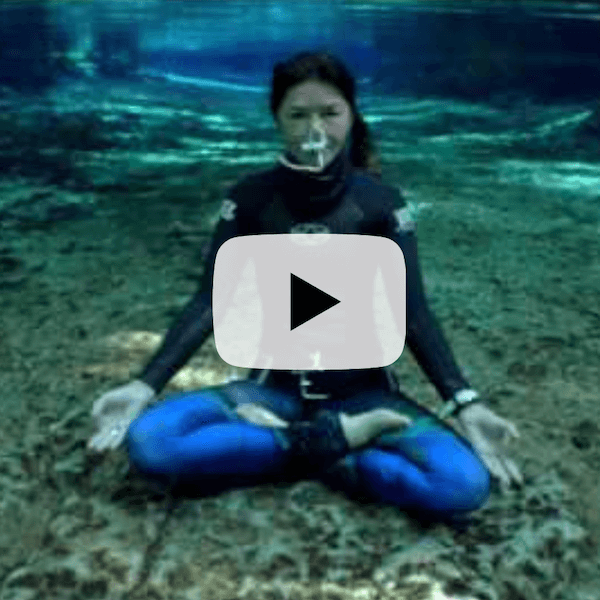

I could see through my mask that the end of the pool was just a few kicks away. I would somehow have to quickly turn around in order to swim as fast as possible to the other end to finish my scientific diving test. My fins felt clunky as I approached the pool wall, and a flip turn did not seem possible. I reached the end, pulled myself upright and slowly turned my body to finish the last length. I could hear a muffled voice screaming, “Faster Cinda, faster! You aren’t going to make it!”. I put my head down and kicked as fast as I could to the other side of the pool where I could tell the other people had already finished. I heard the sound of people screaming my name, but as I touched the pool wall, the Dive Safety Officer bent down and told me, “You are 20 seconds late, you do not pass”. With labored breath, I looked over at the four white men in the pool with me who all arrived in time, then turned my head toward the water and prayed that no one could see the tears welling up in my eyes through my mask.

“If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.”– Shirley Chisholm

I could see through my mask that the end of the pool was just a few kicks away. I would somehow have to quickly turn around in order to swim as fast as possible to the other end to finish my scientific diving test. My fins felt clunky as I approached the pool wall, and a flip turn did not seem possible. I reached the end, pulled myself upright and slowly turned my body to finish the last length. I could hear a muffled voice screaming, “Faster Cinda, faster! You aren’t going to make it!”. I put my head down and kicked as fast as I could to the other side of the pool where I could tell the other people had already finished. I heard the sound of people screaming my name, but as I touched the pool wall, the Dive Safety Officer bent down and told me, “You are 20 seconds late, you do not pass”. With labored breath, I looked over at the four white men in the pool with me who all arrived in time, then turned my head toward the water and prayed that no one could see the tears welling up in my eyes through my mask.

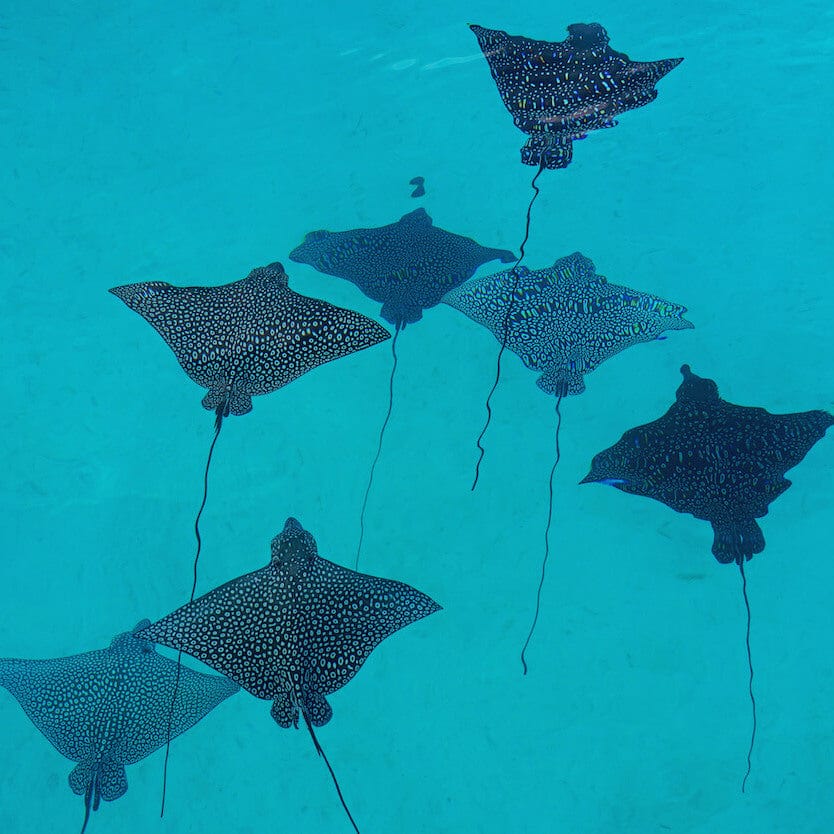

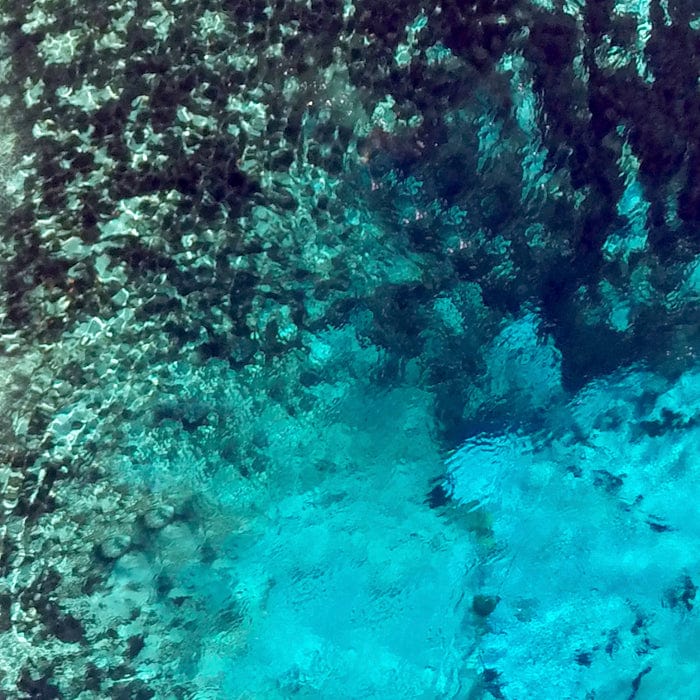

Exploring the reefs of Tanzania off the coast of Zanzibar. Diving brings me a great sense of freedom.

Exploring the reefs of Tanzania off the coast of Zanzibar. Diving brings me a great sense of freedom.

Several days later, I went to the dive office to discuss next steps. Certainly, I would just take the test again I thought. Instead, I was somehow convinced that taking the test again would be a waste of time since my research did not directly involve diving on a regular basis. I was crushed. I also at the time did not realize that I would miss out on the opportunity to dive with my peers to support their research. At the time I wondered, how am I going to become a marine biologist if I could not pass the scientific dive test? Maybe I am not cut out for marine biology after all? Convinced that there was no need to push the issue, I remained silent in my frustration and embarrassment for years.

I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts in the 1980s. My parents moved our family from Boston to the ‘burbs in the late 70s to ensure that my brother and I would have a solid education and that we could grow up to understand that the world was filled with limitless possibilities; which my parents feared would be taken away from us if we remained in the city. My childhood was idyllic. My father took me birding, I learned to swim at a young age, we planted mint, blueberries and a pear tree in the backyard and on any given summer evening you could find a gaggle of “Springdale Road” kids zooming around our cul-de-sacs on Schwinn banana seat bikes until the town lights came on precisely at 9pm. I was raised as part of a community of upwardly mobile black professionals who moved from the south to the north during the Great Migration in search of better opportunity and education. In my household, the role of the child was to do as best as possible in school and education was sacrosanct. At an early age it was instilled in me that I was capable of doing great things. However, though I had familial and economic support to achieve my goals, I was constantly bombarded with images, comments and reminders that I was an outlier.

Several days later, I went to the dive office to discuss next steps. Certainly, I would just take the test again I thought. Instead, I was somehow convinced that taking the test again would be a waste of time since my research did not directly involve diving on a regular basis. I was crushed. I also at the time did not realize that I would miss out on the opportunity to dive with my peers to support their research. At the time I wondered, how am I going to become a marine biologist if I could not pass the scientific dive test? Maybe I am not cut out for marine biology after all? Convinced that there was no need to push the issue, I remained silent in my frustration and embarrassment for years.

I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts in the 1980s. My parents moved our family from Boston to the ‘burbs in the late 70s to ensure that my brother and I would have a solid education and that we could grow up to understand that the world was filled with limitless possibilities; which my parents feared would be taken away from us if we remained in the city. My childhood was idyllic. My father took me birding, I learned to swim at a young age, we planted mint, blueberries and a pear tree in the backyard and on any given summer evening you could find a gaggle of “Springdale Road” kids zooming around our cul-de-sacs on Schwinn banana seat bikes until the town lights came on precisely at 9pm. I was raised as part of a community of upwardly mobile black professionals who moved from the south to the north during the Great Migration in search of better opportunity and education. In my household, the role of the child was to do as best as possible in school and education was sacrosanct. At an early age it was instilled in me that I was capable of doing great things. However, though I had familial and economic support to achieve my goals, I was constantly bombarded with images, comments and reminders that I was an outlier.

I learned to bird with my father at a very young age. Exposure, access, and community and family support helped me grow my appreciation for and love of the natural world.

I learned to bird with my father at a very young age. Exposure, access, and community and family support helped me grow my appreciation for and love of the natural world.

Inequity in access to quality education is by far one of the greatest ills in our society. The history of segregation and its impact on modern day education is most readily seen in school fiscal inequality, student access to quality teachers and curriculum, and implicit biases held by teachers and administrators1,2. The persistent and gaping educational divide limits economic and professional opportunities and denies poor, and black and brown people access to highly specialized fields such as marine biology, conservation biology and scuba diving. The consistent exclusion for generations of black and brown people to quality education has created a chasm so great that many of us simply give up when we do not have the support we need to achieve success. If we want to see more people of color in marine science, policy and conservation institutions, then we must address the educational barriers and exclusionary practices upheld in these fields. My experience trying to obtain a scientific diving license is one small example of such barriers. I was already an adult at that point; but the limitations and obstacles had started much earlier. In the sixth grade, I was removed from my regular English class and placed in the remedial reading room. After about a week, I went home and told my father that I had been moved. I had no idea why I was moved, but the memory of this event is forever seared in my brain. At eleven years old, I watched my father unleash a fury on the school administration the likes of which I had never seen. Not only had I been moved without permission, but there was little evidence to support the move. The next day, I was moved back to my regular English class. I remember feeling a sense of relief and affirmation that I was capable of remaining with the “normal” kids. The effect of just one week in the remedial room damaged my self-esteem and for the first time in my young life, I questioned if I was smart and why I was treated differently. I was lucky. I had parents who knew how to fight against a system that was designed to keep me and thousands of other children like me from academic advancement. My parents also knew how to advocate for me. For children without this type of support, the results are devastating. Just imagine how these education gaps affect entire generations of elementary age or younger, black and brown children.

Inequity in access to quality education is by far one of the greatest ills in our society. The history of segregation and its impact on modern day education is most readily seen in school fiscal inequality, student access to quality teachers and curriculum, and implicit biases held by teachers and administrators1,2. The persistent and gaping educational divide limits economic and professional opportunities and denies poor, and black and brown people access to highly specialized fields such as marine biology, conservation biology and scuba diving. The consistent exclusion for generations of black and brown people to quality education has created a chasm so great that many of us simply give up when we do not have the support we need to achieve success. If we want to see more people of color in marine science, policy and conservation institutions, then we must address the educational barriers and exclusionary practices upheld in these fields. My experience trying to obtain a scientific diving license is one small example of such barriers. I was already an adult at that point; but the limitations and obstacles had started much earlier. In the sixth grade, I was removed from my regular English class and placed in the remedial reading room. After about a week, I went home and told my father that I had been moved. I had no idea why I was moved, but the memory of this event is forever seared in my brain. At eleven years old, I watched my father unleash a fury on the school administration the likes of which I had never seen. Not only had I been moved without permission, but there was little evidence to support the move. The next day, I was moved back to my regular English class. I remember feeling a sense of relief and affirmation that I was capable of remaining with the “normal” kids. The effect of just one week in the remedial room damaged my self-esteem and for the first time in my young life, I questioned if I was smart and why I was treated differently. I was lucky. I had parents who knew how to fight against a system that was designed to keep me and thousands of other children like me from academic advancement. My parents also knew how to advocate for me. For children without this type of support, the results are devastating. Just imagine how these education gaps affect entire generations of elementary age or younger, black and brown children.

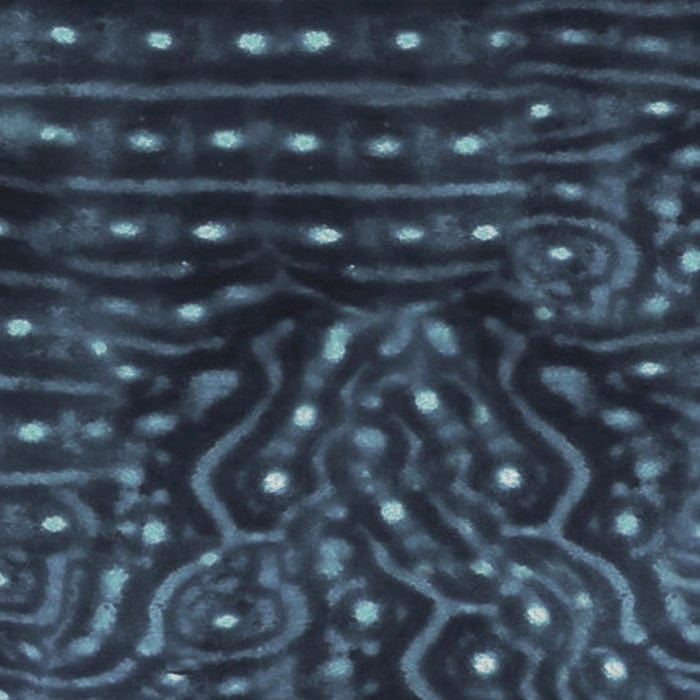

My journey in the field of marine biology has at times felt isolating, but my connection to and curiosity of the natural world has provided strength and guidance along the way.

My journey in the field of marine biology has at times felt isolating, but my connection to and curiosity of the natural world has provided strength and guidance along the way.

The education gap has consequences for us all

In the US, out-of-school suspensions are 3.6 times more likely for black preschool children than white preschool children, black and Latinx high school students have decreased access to high-level science and math courses and it is estimated that 56% of college students enrolled in remedial courses are black, thereby hindering their ability to complete higher degrees in four years and subjecting them to higher educational costs 3,4.

As I have pointed out, for people of color, barriers to education exist everywhere. For those of us who do not fit standard molds of what is expected in particular spaces, those barriers can seem ever growing and sporadic, and can appear out of nowhere. The placement of these barriers not only impacts students in K-12 and higher education systems, but also limits our ability to solve some of the world’s most threatening environmental problems. Why? Because science is seen as fundamental to addressing global environmental issues. Unfortunately, more than other fields, geosciences systematically excludes people of color and minoritized groups. The statistics on how many black students complete a Ph.D. in ocean sciences is startling. The most recent data from the 2016 NSF report on Women, Minorities and Persons with Disabilities finds that of the 620,489 total enrolled science and engineering graduate student population, only 36 (0.1%) were in ocean sciences. When broken down further by sex, of the 17,630 enrolled black female graduate students, 551 studied biology and only 18 ocean science, representing <0.1% and <0.003% of the entire enrolled science and engineering graduate student population, respectively 5.

The education gap has consequences for us all

In the US, out-of-school suspensions are 3.6 times more likely for black preschool children than white preschool children, black and Latinx high school students have decreased access to high-level science and math courses and it is estimated that 56% of college students enrolled in remedial courses are black, thereby hindering their ability to complete higher degrees in four years and subjecting them to higher educational costs 3,4.

As I have pointed out, for people of color, barriers to education exist everywhere. For those of us who do not fit standard molds of what is expected in particular spaces, those barriers can seem ever growing and sporadic, and can appear out of nowhere. The placement of these barriers not only impacts students in K-12 and higher education systems, but also limits our ability to solve some of the world’s most threatening environmental problems. Why? Because science is seen as fundamental to addressing global environmental issues. Unfortunately, more than other fields, geosciences systematically excludes people of color and minoritized groups. The statistics on how many black students complete a Ph.D. in ocean sciences is startling. The most recent data from the 2016 NSF report on Women, Minorities and Persons with Disabilities finds that of the 620,489 total enrolled science and engineering graduate student population, only 36 (0.1%) were in ocean sciences. When broken down further by sex, of the 17,630 enrolled black female graduate students, 551 studied biology and only 18 ocean science, representing <0.1% and <0.003% of the entire enrolled science and engineering graduate student population, respectively 5.

Beyond Academia, the glaring lack of diversity in US conservation organizations was addressed head-on by Dr. Dorceta Taylor of the University of Michigan’s School for Environment and Sustainability, in her 2014 report, “The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations: Mainstream NGOs, Foundations, and Government Agencies” 6. In a recent online workshop I attended with Dr. Taylor, she discussed openly how the gross underrepresentation of people of color in conservation is emblematic of the larger problem of systemic racism, especially with regard to decision-making. She also touched on how too often the misconception that black people do not care about the environment is upheld in depictions of urban, poor communities where elimination of green spaces is rampant, thereby solidifying a sense of non-belonging in the natural world. Additionally, people of color are often blamed for our collective environmental woes and yet are forced on the front lines of the fight for clean air, safe drinking water and adapting to the climate crisis. This is highlighted in a 2019 study that found “pollution inequity” is more severely felt by blacks and Hispanics and continues to remain high in these populations 7.

Beyond Academia, the glaring lack of diversity in US conservation organizations was addressed head-on by Dr. Dorceta Taylor of the University of Michigan’s School for Environment and Sustainability, in her 2014 report, “The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations: Mainstream NGOs, Foundations, and Government Agencies” 6. In a recent online workshop I attended with Dr. Taylor, she discussed openly how the gross underrepresentation of people of color in conservation is emblematic of the larger problem of systemic racism, especially with regard to decision-making. She also touched on how too often the misconception that black people do not care about the environment is upheld in depictions of urban, poor communities where elimination of green spaces is rampant, thereby solidifying a sense of non-belonging in the natural world. Additionally, people of color are often blamed for our collective environmental woes and yet are forced on the front lines of the fight for clean air, safe drinking water and adapting to the climate crisis. This is highlighted in a 2019 study that found “pollution inequity” is more severely felt by blacks and Hispanics and continues to remain high in these populations 7.

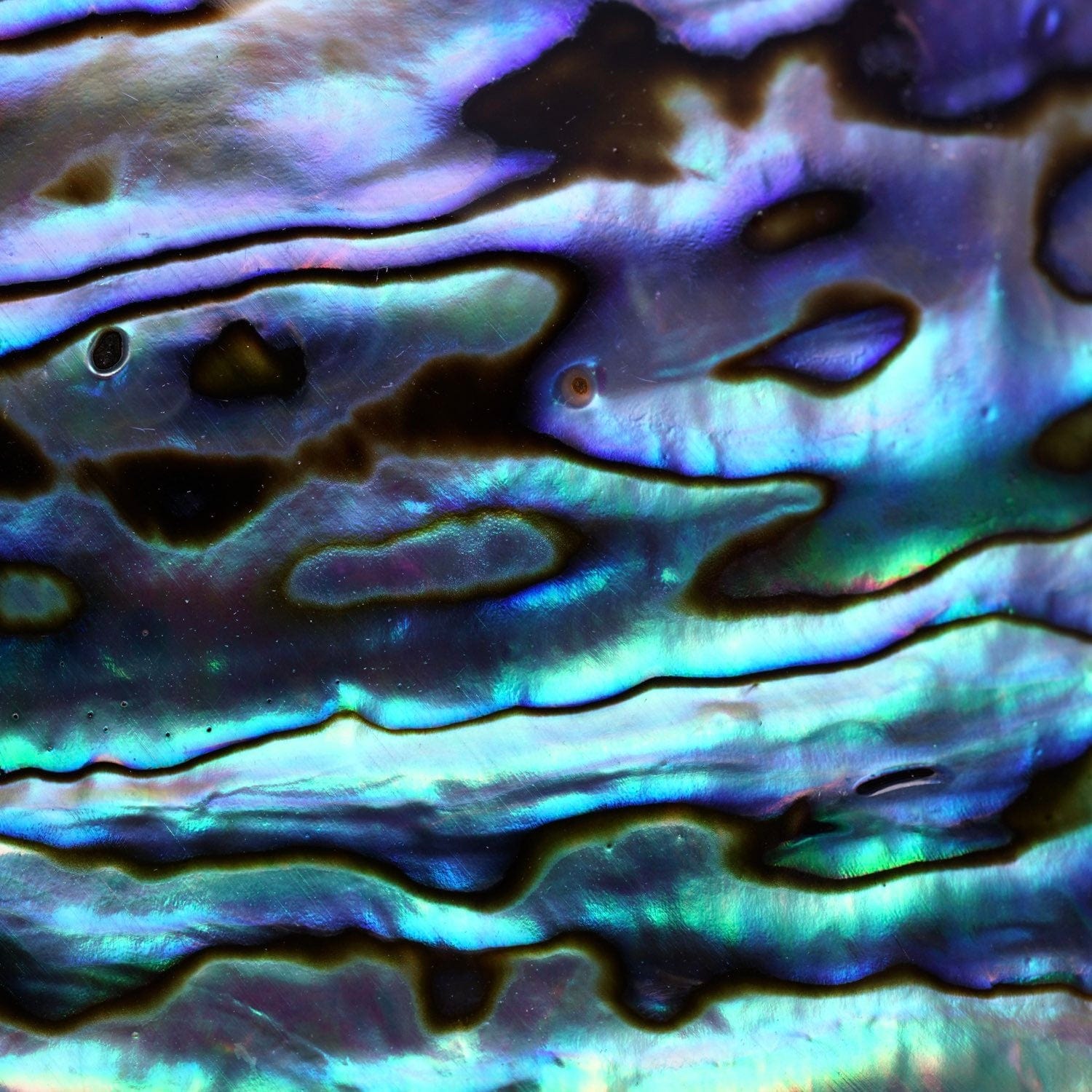

Helping to protect marine ecosystems such as those of the Isla Bastimentos National Marine Park in Bocas del Toro, Panama is an important and central part of my work. Ensuring that all people have access to natural spaces is important to me.

Decolonizing conservation

I currently serve as the Center Director for The School for Field Studies, Center for Tropical Island Biodiversity Studies. I work at the intersection of teaching, administration, research and conservation. My research on mangrove habitat complexity has helped guide conversations around future policies for marine protected area expansion in the Bocas del Toro archipelago in Panama. As a member of the Bocas community, I am keenly aware that conservation is not possible without the involvement of local people, organizations and government agencies. Too often, NGOs, many with good intentions, make the fatal error of excluding local people, entities and agencies, in their attempt to do what they consider “conservation”. Modern models of conservation still use neocolonial frameworks entrenched in racist ideals that were purposely designed to remove people from natural spaces to protect the wild8,9. Continued denial of the right to land and areas with cultural significance to the people who depend upon it is at the core of conservation and must be reckoned with. In my own work, in understanding that marine protected areas around the globe are largely ineffective (59%) and actively deny people access to protein, I am confronted with and conflicted by the continued promulgation of a flawed system. It is this base in exclusive neocolonial conservation values that allows access to MPAs for scuba divers, snorkelers and tourists who have the economic mobility to enjoy them in the name of economic gain10.For example, a recent study of tourists visiting the Isla Bastimentos National Marine Park in Bocas del Toro, Panama, found that 74% of visitors were from Europe or North America11.

Who is the environment for?

Far too often, the message is that the natural world is not meant for black and brown people. The more that message is spread, and the more we are invisibilized in these fields and in media pertaining to these fields, the more we are taught to believe it is true. During a brief summer internship at a major national conservation organization, I was the only black person at the office headquarters. Though many conservation organizations operating worldwide have a very diverse staff, my personal observation and experience is that the offices in which the people in positions of power, and who serve in the administrative offices where major decisions are made, are severely lacking in diverse workforces. The invisible message becomes quite visible when trying to traverse becoming a professional in conservation. Models of exclusion are seen and practiced around the globe enrobed in the name of conservation and must change if we are to see any progress in diversifying.

Decolonizing conservation

I currently serve as the Center Director for The School for Field Studies, Center for Tropical Island Biodiversity Studies. I work at the intersection of teaching, administration, research and conservation. My research on mangrove habitat complexity has helped guide conversations around future policies for marine protected area expansion in the Bocas del Toro archipelago in Panama. As a member of the Bocas community, I am keenly aware that conservation is not possible without the involvement of local people, organizations and government agencies. Too often, NGOs, many with good intentions, make the fatal error of excluding local people, entities and agencies, in their attempt to do what they consider “conservation”. Modern models of conservation still use neocolonial frameworks entrenched in racist ideals that were purposely designed to remove people from natural spaces to protect the wild8,9. Continued denial of the right to land and areas with cultural significance to the people who depend upon it is at the core of conservation and must be reckoned with. In my own work, in understanding that marine protected areas around the globe are largely ineffective (59%) and actively deny people access to protein, I am confronted with and conflicted by the continued promulgation of a flawed system. It is this base in exclusive neocolonial conservation values that allows access to MPAs for scuba divers, snorkelers and tourists who have the economic mobility to enjoy them in the name of economic gain10.For example, a recent study of tourists visiting the Isla Bastimentos National Marine Park in Bocas del Toro, Panama, found that 74% of visitors were from Europe or North America11.

Who is the environment for?

Far too often, the message is that the natural world is not meant for black and brown people. The more that message is spread, and the more we are invisibilized in these fields and in media pertaining to these fields, the more we are taught to believe it is true. During a brief summer internship at a major national conservation organization, I was the only black person at the office headquarters. Though many conservation organizations operating worldwide have a very diverse staff, my personal observation and experience is that the offices in which the people in positions of power, and who serve in the administrative offices where major decisions are made, are severely lacking in diverse workforces. The invisible message becomes quite visible when trying to traverse becoming a professional in conservation. Models of exclusion are seen and practiced around the globe enrobed in the name of conservation and must change if we are to see any progress in diversifying.

Feeling welcomed and accepted as part of the larger diving and marine science community is important in ensuring students of color can make the necessary steps toward degree completion. Exploring the reefs of the Dominican Republic. Photo by Dr. Heidi Hertler.

Feeling welcomed and accepted as part of the larger diving and marine science community is important in ensuring students of color can make the necessary steps toward degree completion. Exploring the reefs of the Dominican Republic. Photo by Dr. Heidi Hertler.

I started my graduate career in the trough of a wave that at the time seemed insurmountable to swim out of. I chose a career in the field of marine biology because I truly was interested in understanding life at a molecular level as it pertained to marine organisms. I arrived at graduate school as well equipped as possible, but I was already behind in comparison to my white peers. However, I refused to remain at the rear. My drive came from the support of family, friends and professors who were allies, and the need to prove to myself and the world that the environment is for everyone.

In my current line of work, I often receive college students studying abroad in environmental studies who are not well equipped for the rigors of the program. They arrive with no snorkeling or swimming skills and 99% of the time those students are my only students of color in the program. From the beginning they arrive with a severe disadvantage much the same way I arrived to graduate school without the background or experience in how to be in the water. Instead of getting ahead on their academic assignments like the rest of their peers at the start of the program, they are stuck in the pool with me going over the breast stroke and the front crawl so that they can pass the swim test and freely, and joyfully experience the joy of snorkeling and paddle boarding. Many of the students who do the swim test cry when they do not pass, and I am whisked back to my own failure at the scientific diving swim test. My first words to them are, “Okay, so you did not pass. I will give you a few moments to stop crying, and then we will work together to figure out how to get you to where you need to be.” I purposely change the narrative so that my students know that I support them and so that they can find the inner strength to continue. This was not afforded to me on that fateful day I failed my scientific dive swim test. “You do not pass” should not mean that you will never or that you are not worth investing in. Providing quality education means that you get in the pool with your students. You show up to support them and you invest in them because you know that they are capable of changing the world. “You do not pass” should not mean that you are barred or forever excluded from your passion.

I started my graduate career in the trough of a wave that at the time seemed insurmountable to swim out of. I chose a career in the field of marine biology because I truly was interested in understanding life at a molecular level as it pertained to marine organisms. I arrived at graduate school as well equipped as possible, but I was already behind in comparison to my white peers. However, I refused to remain at the rear. My drive came from the support of family, friends and professors who were allies, and the need to prove to myself and the world that the environment is for everyone.

In my current line of work, I often receive college students studying abroad in environmental studies who are not well equipped for the rigors of the program. They arrive with no snorkeling or swimming skills and 99% of the time those students are my only students of color in the program. From the beginning they arrive with a severe disadvantage much the same way I arrived to graduate school without the background or experience in how to be in the water. Instead of getting ahead on their academic assignments like the rest of their peers at the start of the program, they are stuck in the pool with me going over the breast stroke and the front crawl so that they can pass the swim test and freely, and joyfully experience the joy of snorkeling and paddle boarding. Many of the students who do the swim test cry when they do not pass, and I am whisked back to my own failure at the scientific diving swim test. My first words to them are, “Okay, so you did not pass. I will give you a few moments to stop crying, and then we will work together to figure out how to get you to where you need to be.” I purposely change the narrative so that my students know that I support them and so that they can find the inner strength to continue. This was not afforded to me on that fateful day I failed my scientific dive swim test. “You do not pass” should not mean that you will never or that you are not worth investing in. Providing quality education means that you get in the pool with your students. You show up to support them and you invest in them because you know that they are capable of changing the world. “You do not pass” should not mean that you are barred or forever excluded from your passion.

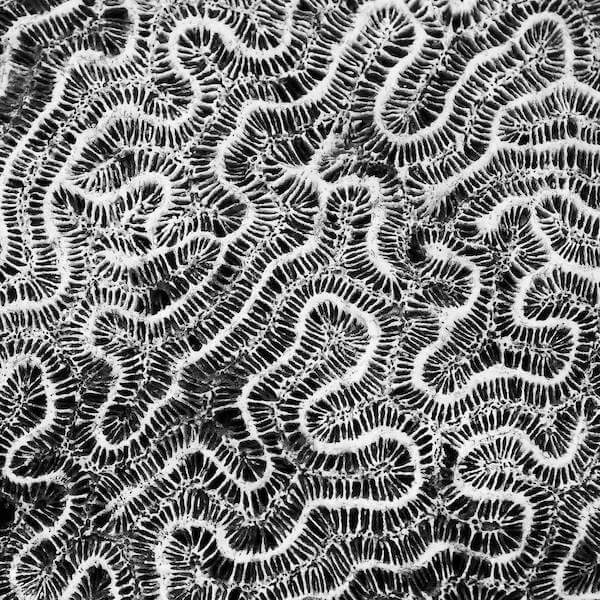

Teaching research in the field with my students is my greatest joy.

The Way Forward

When I was near the completion of my Ph.D., my mom threw a small party for me at a local beach just north of South Beach. We rented a few of the shelters with a bar-b-que pit and I invited friends, family and professors to attend. While chatting with a professor, he said to me, “Wow, it is amazing how many people flew all the way here to celebrate your graduation. When I graduated, I certainly did not receive this much fanfare.” I smiled gently and I said, “It’s not every day that a black female finishes a Ph.D. in marine biology. The Beantown crew shows up for each of us kids when we finish a degree.” My matter of fact delivery left him with nothing more to say so I turned away and walked back to where my mom was sitting with my aunties and uncles and family friends who had flown to Miami from Boston to celebrate my achievement. I looked around the table and my heart was filled with pride as I listened to the boisterous chatter of eight black Ph.D.s of different generations enjoying the moment. My Uncle Alvin has always been my number one cheerleader and he has attended every single graduation I have ever had. He is also the loudest person on the planet and as my aunt Lydia shushed him to pipe down, he protested by saying, “Why should I, how often does this happen?”. He stood up to give me a hug and my face smooshed against his chest. With one eye, I could see the ocean and in the comfort of his embrace, he continued to laugh as loud as ever in concert with the sea.

My journey to becoming a marine biologist has been both tumultuous and glorious. I have learned to never give up, rely on my inner strength, and to bring my own folding chair when necessary. I became an advanced, scientific and rescue diver at 37 years old.

As we continue our collective journey together to understand and rectify historically entrenched racist policies in the United States, and as we try as scientists to salvage what remains of some of the earth’s most fragile and important ecosystems, let us remember that each of us has the responsibility to invest in, foster and support black students to reach the highest levels of academia. Our very future depends on it.

How can you support young people of color pursuing degrees in environmental studies, marine biology and conservation?

- Believe in them. Show them that you believe in them by telling them that they are capable and that they can do the work.

- Get in the pool! Support them with your presence. Show up. Encourage them to keep trying.

- Diversify the narrative. Stop using material or curriculum that is comfortable only for you. Explore other narratives and change the story.

- Be an ally. Fight against systems of oppression and educate yourself on barriers to access to education for students of color. Know what your implicit biases are and make steps to change them.

- Educate yourself. Science and conservation are not immune to the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow. The very people who are deemed ill fit for marine biology, conservation and environmental studies may be the very minds who have the ideas, perspectives and knowledge to solve some of the world’s most threatening issues. When black and brown people are excluded and left out, not only are they denied access and opportunity, but society as a whole does not receive the gift of their bright minds working together to help change the world.

- Change your spending habits. Stop supporting companies and industries that oppress people and the environment, and those who use their political power to support and uphold racist policies.

- End racist policies. Use your vote, your dollars and your voice to end decades-old racist policies in health care, education, environmental issues, the criminal justice system and in our economy that are upheld by the notion that blacks and other people of color are inferior to whites.

Systemic change is needed urgently in all sectors of society where racism pervades. Academia is no exception and the need for change is high. This is not just a university or departmental issue, it is at its core a matter of people treating other people with dignity and respect, and reversing waves of inequality that have been entrenched in our educational system for centuries. If we can embrace the immense diversity found across thousands of species, then surely, we can learn to accept the beautiful diversity that exists within our own.

References

- Kozol, Jonathan. Savage Inequalities: Children in America's Schools. Broadway Paperbacks, 2012.

- Meatto, Keith. “Still Separate, Still Unequal: Teaching about School Segregation and Educational Inequality.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 2 May 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/05/02/learning/lesson-plans/still-separate-still-unequal-teaching-about-school-segregation-and-educational-inequality.html.

- Laura Jimenez, Scott Sargrad. “Remedial Education.” Center for American Progress, www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/reports/2016/09/28/144000/remedial-education/.The Cost of Catching Up, Jimenez et. Al, 2016 from Complete College America, “Corequisite Remediation: Spanning the Completion Divide,” available at http://completecollege.org/spanningthedivide/#home (last accessed May 2016).

- US Dept of Education Office for Civil Rights 2016 release “2013-2014 Civil Rights Data Collection, A First Look, Key Data Highlights on Equity and Opportunity Gaps in our Nation’s Public Schools”, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/2013-14-first-look.pdf

- “2019 Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities Report Goes Live.” NSF, www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=297944.Retrieved June 13, 2020, https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19304/

- The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations. http://www.diversegreen.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/FullReport_Green2.0_FINAL.pdf

- Tessum, Christopher W., et al. “Inequity in Consumption of Goods and Services Adds to Racial–Ethnic Disparities in Air Pollution Exposure.” PNAS, National Academy of Sciences, 26 Mar. 2019, www.pnas.org/content/116/13/6001.

- Purdy, Jedediah, et al. “Environmentalism's Racist History.” The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/environmentalisms-racist-history

- Mbaria, John, and Mordecai Ogada. The Big Conservation Lie: the Untold Story of Wildlife Conservation in Kenya. Lens Et Pens Publishing, 2017.

- Edgar, Graham J., et al. “Global Conservation Outcomes Depend on Marine Protected Areas with Five Key Features.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 5 Feb. 2014, https://www.nature.com/articles/nature13022.

- Mach, Leon, et al. “Protected Area Entry Fees and Governance Quality.” Tourism Management, vol. 77, 2020, p. 104003., doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104003.

The Way Forward

When I was near the completion of my Ph.D., my mom threw a small party for me at a local beach just north of South Beach. We rented a few of the shelters with a bar-b-que pit and I invited friends, family and professors to attend. While chatting with a professor, he said to me, “Wow, it is amazing how many people flew all the way here to celebrate your graduation. When I graduated, I certainly did not receive this much fanfare.” I smiled gently and I said, “It’s not every day that a black female finishes a Ph.D. in marine biology. The Beantown crew shows up for each of us kids when we finish a degree.” My matter of fact delivery left him with nothing more to say so I turned away and walked back to where my mom was sitting with my aunties and uncles and family friends who had flown to Miami from Boston to celebrate my achievement. I looked around the table and my heart was filled with pride as I listened to the boisterous chatter of eight black Ph.D.s of different generations enjoying the moment. My Uncle Alvin has always been my number one cheerleader and he has attended every single graduation I have ever had. He is also the loudest person on the planet and as my aunt Lydia shushed him to pipe down, he protested by saying, “Why should I, how often does this happen?”. He stood up to give me a hug and my face smooshed against his chest. With one eye, I could see the ocean and in the comfort of his embrace, he continued to laugh as loud as ever in concert with the sea.

My journey to becoming a marine biologist has been both tumultuous and glorious. I have learned to never give up, rely on my inner strength, and to bring my own folding chair when necessary. I became an advanced, scientific and rescue diver at 37 years old.

As we continue our collective journey together to understand and rectify historically entrenched racist policies in the United States, and as we try as scientists to salvage what remains of some of the earth’s most fragile and important ecosystems, let us remember that each of us has the responsibility to invest in, foster and support black students to reach the highest levels of academia. Our very future depends on it.

How can you support young people of color pursuing degrees in environmental studies, marine biology and conservation?

- Believe in them. Show them that you believe in them by telling them that they are capable and that they can do the work.

- Get in the pool! Support them with your presence. Show up. Encourage them to keep trying.

- Diversify the narrative. Stop using material or curriculum that is comfortable only for you. Explore other narratives and change the story.

- Be an ally. Fight against systems of oppression and educate yourself on barriers to access to education for students of color. Know what your implicit biases are and make steps to change them.

- Educate yourself. Science and conservation are not immune to the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow. The very people who are deemed ill fit for marine biology, conservation and environmental studies may be the very minds who have the ideas, perspectives and knowledge to solve some of the world’s most threatening issues. When black and brown people are excluded and left out, not only are they denied access and opportunity, but society as a whole does not receive the gift of their bright minds working together to help change the world.

- Change your spending habits. Stop supporting companies and industries that oppress people and the environment, and those who use their political power to support and uphold racist policies.

- End racist policies. Use your vote, your dollars and your voice to end decades-old racist policies in health care, education, environmental issues, the criminal justice system and in our economy that are upheld by the notion that blacks and other people of color are inferior to whites.

Systemic change is needed urgently in all sectors of society where racism pervades. Academia is no exception and the need for change is high. This is not just a university or departmental issue, it is at its core a matter of people treating other people with dignity and respect, and reversing waves of inequality that have been entrenched in our educational system for centuries. If we can embrace the immense diversity found across thousands of species, then surely, we can learn to accept the beautiful diversity that exists within our own.

References

- Kozol, Jonathan. Savage Inequalities: Children in America's Schools. Broadway Paperbacks, 2012.

- Meatto, Keith. “Still Separate, Still Unequal: Teaching about School Segregation and Educational Inequality.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 2 May 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/05/02/learning/lesson-plans/still-separate-still-unequal-teaching-about-school-segregation-and-educational-inequality.html.

- Laura Jimenez, Scott Sargrad. “Remedial Education.” Center for American Progress, www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/reports/2016/09/28/144000/remedial-education/.The Cost of Catching Up, Jimenez et. Al, 2016 from Complete College America, “Corequisite Remediation: Spanning the Completion Divide,” available at http://completecollege.org/spanningthedivide/#home (last accessed May 2016).

- US Dept of Education Office for Civil Rights 2016 release “2013-2014 Civil Rights Data Collection, A First Look, Key Data Highlights on Equity and Opportunity Gaps in our Nation’s Public Schools”, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/2013-14-first-look.pdf

- “2019 Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities Report Goes Live.” NSF, www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=297944.Retrieved June 13, 2020, https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19304/

- The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations. http://www.diversegreen.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/FullReport_Green2.0_FINAL.pdf

- Tessum, Christopher W., et al. “Inequity in Consumption of Goods and Services Adds to Racial–Ethnic Disparities in Air Pollution Exposure.” PNAS, National Academy of Sciences, 26 Mar. 2019, www.pnas.org/content/116/13/6001.

- Purdy, Jedediah, et al. “Environmentalism's Racist History.” The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/environmentalisms-racist-history

- Mbaria, John, and Mordecai Ogada. The Big Conservation Lie: the Untold Story of Wildlife Conservation in Kenya. Lens Et Pens Publishing, 2017.

- Edgar, Graham J., et al. “Global Conservation Outcomes Depend on Marine Protected Areas with Five Key Features.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 5 Feb. 2014, https://www.nature.com/articles/nature13022.

- Mach, Leon, et al. “Protected Area Entry Fees and Governance Quality.” Tourism Management, vol. 77, 2020, p. 104003., doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104003.

Dr. Cinda Scott is a marine biologist and Director of The School for Field Studies (SFS) Center for Tropical Island Biodiversity Studies in Bocas del Toro, Panamá. SFS provides transformative, environmental study abroad experiences for undergraduate students. Dr. Scott’s research focuses on mangrove habitat complexity and she is dedicated to shaping and growing the next generation of marine, conservation and policy scientists. You can stay up to date on her travels and interests by visiting her website www.cindaseas.world.

Claudette Dorsey

September 20, 2020

Dr. Scott,

Thank you for all of this. Your voice, your science, and your passionate knowledge are changing the world and will affect more people than you’ll ever know. Thank you for this strongly referenced description of racism in the sciences. And thank you for the list of seven actionable ways to support young people of color in the sciences. (Thank you, Waterlust, for amplifying Dr. Scott’s critically needed voice on this channel.)