In a past life, I used to live on the small island of Eleuthera in The Bahamas. Two or three times a week, a local Bahamian fisherman named Larry and I would pull around eighty 3-foot-long cobia from a net pen installed about a mile offshore there.Back at the dock, we would fillet them on a fish cleaning table and occasionally toss a scrap piece into the water to watch the fish eat it.

Many of the men there are fishermen and it’s an important source of food and income for the community. Larry would tell me about how the catches are doing and where his favorite spots are. He targets conch and lobster, but also takes grouper and snapper. “Catches are good” he says, “but you never know when you’re going to have a bad day”. He likes working with us mainly for a change in his routine and some socializing but also the reliability of harvesting fish out of a pen. Larry and I will take the whole afternoon filleting the fish, packing them into zip lock bags, and dropping them off in the kitchen at the school and research institute that I work at. Larry gets a bag of fish and $50 for his help and the rest of the fish will be eaten by the students and staff there.

It’s a good feeling to provide food for your community.

In a past life, I used to live on the small island of Eleuthera in The Bahamas. Two or three times a week, a local Bahamian fisherman named Larry and I would pull around eighty 3-foot-long cobia from a net pen installed about a mile offshore there.Back at the dock, we would fillet them on a fish cleaning table and occasionally toss a scrap piece into the water to watch the fish eat it.

Many of the men there are fishermen and it’s an important source of food and income for the community. Larry would tell me about how the catches are doing and where his favorite spots are. He targets conch and lobster, but also takes grouper and snapper. “Catches are good” he says, “but you never know when you’re going to have a bad day”. He likes working with us mainly for a change in his routine and some socializing but also the reliability of harvesting fish out of a pen. Larry and I will take the whole afternoon filleting the fish, packing them into zip lock bags, and dropping them off in the kitchen at the school and research institute that I work at. Larry gets a bag of fish and $50 for his help and the rest of the fish will be eaten by the students and staff there.

It’s a good feeling to provide food for your community.

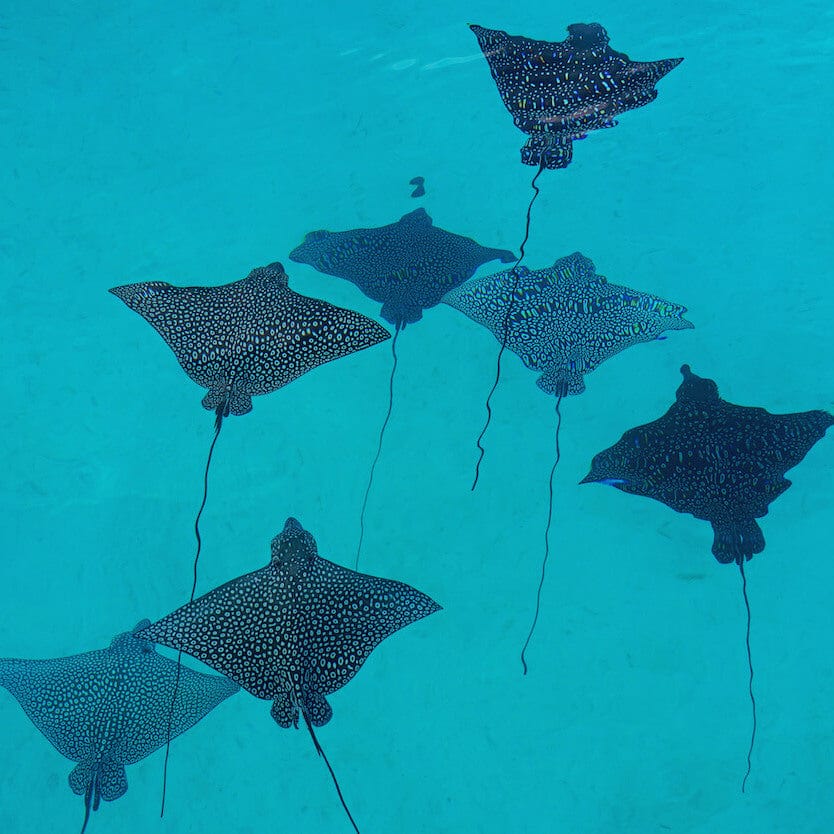

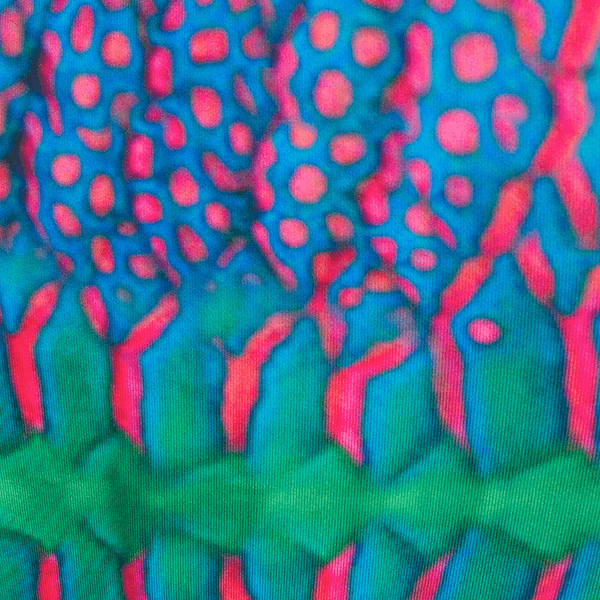

Photo by Tyler Sclodnick of cobia swimming in a SeaStation aquaculture pen at theCape Eleuthera Institute in The Bahamas

I work in Aquaculture.When I tell people this the most common response is “Aquaculture… but isn’t that bad?”.

Not everyone asks this, but the sentiment is certainly the most common.“I thought you were saving the oceans or something”, might come from people who knew me when I was an undergraduate focused on marine conservation.

I did work in marine conservation for a few years as was the plan when I graduated university. The switch to aquaculture came not because I was tired of low salaries or long days in the field (frankly, at the time I was pretty excited about the $12,000 per year plus room and board job that I had landed at a research facility) but rather because I felt that aquaculture might be one of the most powerful conservation tools that we have.

Economics could save the environment.

Before exploring that thought, I need to acknowledge that aquaculture can have detrimental impacts on the environment if not done responsibly, but this is not intrinsic to aquaculture, nor is it the norm. It is important to evaluate industries and hold them accountable to a standard, but this should be done fairly and objectively. It doesn’t make sense to say “agriculture is bad” just because certain farmers pack their livestock too tightly. Agriculture is good even if a certain method of farming needs reform.

Aquaculture is an extremely diverse industry. In fact, the word “Aquaculture” describes the production of a vastly more diverse array of organisms than those farmed on land. On top of fish, there are large and profitable industries producing shrimp, mussels, oysters, sea cucumbers, frogs, alligators, kelp, algae and many more. It cannot be boiled down to “aquaculture is good” or “aquaculture is bad” any more than you could say that about land-based farming. A single irresponsible fish farmer is no more representative of the industry than an irresponsible cattle farmer, car manufacturer or utilities supplier represents their industries. They are rare and usually the result of a poor understanding of their actions rather than intentional malicious strategies.

Furthermore, modern aquaculture only really began in the 1980’s making it a very young industry. If we are to build a sustainable industry that can fulfill the promise it has for healthy, sustainable protein production and stable employment in coastal communities, then we will have to go through the learning stages during which the industry will advance how it operates, how it is regulated and how it evaluates itself. Luckily, we’ve improved by leaps and bounds over the last few decades. But on that point, you’ll just have to trust me. Or you can do your own research here, here, here, here or here.

I work in Aquaculture.When I tell people this the most common response is “Aquaculture… but isn’t that bad?”.

Not everyone asks this, but the sentiment is certainly the most common.“I thought you were saving the oceans or something”, might come from people who knew me when I was an undergraduate focused on marine conservation.

I did work in marine conservation for a few years as was the plan when I graduated university. The switch to aquaculture came not because I was tired of low salaries or long days in the field (frankly, at the time I was pretty excited about the $12,000 per year plus room and board job that I had landed at a research facility) but rather because I felt that aquaculture might be one of the most powerful conservation tools that we have.

Economics could save the environment.

Before exploring that thought, I need to acknowledge that aquaculture can have detrimental impacts on the environment if not done responsibly, but this is not intrinsic to aquaculture, nor is it the norm. It is important to evaluate industries and hold them accountable to a standard, but this should be done fairly and objectively. It doesn’t make sense to say “agriculture is bad” just because certain farmers pack their livestock too tightly. Agriculture is good even if a certain method of farming needs reform.

Aquaculture is an extremely diverse industry. In fact, the word “Aquaculture” describes the production of a vastly more diverse array of organisms than those farmed on land. On top of fish, there are large and profitable industries producing shrimp, mussels, oysters, sea cucumbers, frogs, alligators, kelp, algae and many more. It cannot be boiled down to “aquaculture is good” or “aquaculture is bad” any more than you could say that about land-based farming. A single irresponsible fish farmer is no more representative of the industry than an irresponsible cattle farmer, car manufacturer or utilities supplier represents their industries. They are rare and usually the result of a poor understanding of their actions rather than intentional malicious strategies.

Furthermore, modern aquaculture only really began in the 1980’s making it a very young industry. If we are to build a sustainable industry that can fulfill the promise it has for healthy, sustainable protein production and stable employment in coastal communities, then we will have to go through the learning stages during which the industry will advance how it operates, how it is regulated and how it evaluates itself. Luckily, we’ve improved by leaps and bounds over the last few decades. But on that point, you’ll just have to trust me. Or you can do your own research here, here, here, here or here.

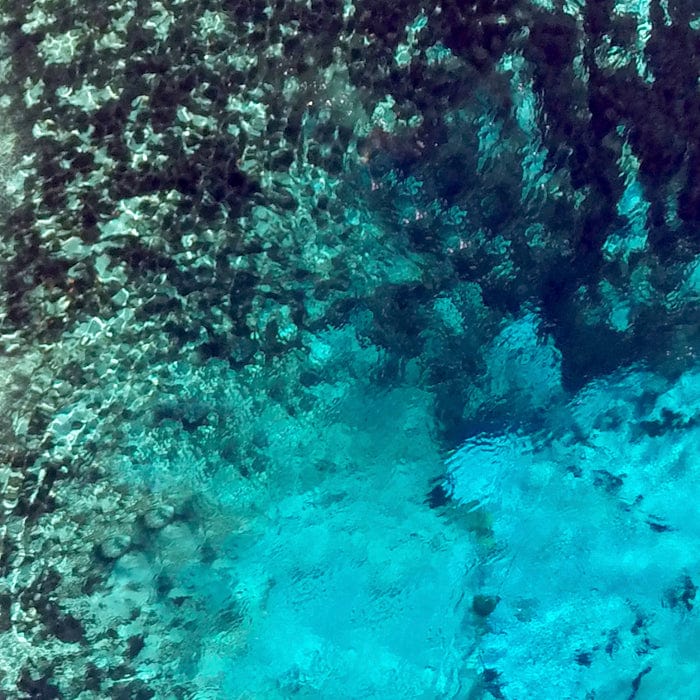

Photo fromInnovasea showing a submerged SeaStation pen stock with fish.

Back to aquaculture as a conservation tool.

As Waterlust founder, Patrick Rynne, discussed in a previous blog post, every product that humans produce has an environmental cost. The objective of an environmentally conscientious producer of anything is to make a product that satisfies the demand for it while creating the lowest ecological impact and staying within the carrying capacity of the environment.

Demand for seafood and protein is expected to climb dramatically over the next few decades. The global population continues to rise, large lower-income populations in China and India are increasing their GDP and adding more protein to their diet, and buying trends in North America and Europe are showing a shift from beef and pork towards chicken and seafood as people seek lower saturated fats in their proteins. Many environmentalists have pushed vegetarianism as a solution to reduce our ecological footprint and eating less meat is undoubtedly a very impactful way to lower your indirect carbon and freshwater consumption and should be encouraged. However, food is a powerful cultural and sociological cornerstone and large-scale dietary shifts do not occur in the timeframe needed to address our immediate marine environment concerns.

As a global strategy, not enough people are changing their eating habits to alleviate the need for lower impact protein production methods. We need alternatives that billions of people will get on board with and soon.

If there was ever a time to make a change in how we produce food, that time is now.In fact, change has been imposed upon us.Both protein producers and consumers all over the world have changed dramatically as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. There are large meat shortages in many countries as processing plants are forced to shutdown due to coronavirus cases. Seafood has seen similar issues although on a smaller scale but have also had to adjust their processes to account for the closing of restaurants where an estimated 70% of seafood is consumed in America. Seafood producers are turning to frozen or portioned and packed product forms to address this, but change doesn’t happen overnight.

Consumers are cooking at home at levels never seen before which leads naturally to a closer examination of one’s diet. Without intending to, I’ve been almost completely pescatarian during the quarantine (just a few pepperoni pizzas away from being able to make that claim without a qualifier) and have been eating vegetarian more often than not. Many of my friends are discovering the joys of bread baking, how quick and healthy oatmeal with berries can be and looking up the astounding nutritional profile of lentils and other pulses. How everything will shake out as businesses re-open is still very much uncertain, but there is no doubt that a shake-up is occurring.

Wild fisheries will continue to be an essential part of seafood production but should not be expected to fill the projected increase in demand. Wild capture fisheries are a finite resource so there are no more available fish to catch. We have maxed out most fisheries ability to replace themselves and, in many cases, should consider reducing catches to allow wild populations to recover.

Seafood is usually a more sustainable protein source than terrestrial protein. There are always exceptions to the rule such as wild-caught species that have high by-catch rates, but aquatic organisms have a few major advantages that make them very efficient to produce.

1) They are cold-blooded, so they don’t spend energy heating their bodies.

2) They don’t fight gravity.

3) They don’t spend energy building dense, heavy bones.

4) Swimming (or being a stationary filter feeder) is more efficient locomotion than walking or flying.

Aquatic organisms generally have better energy retention and protein retention capabilities than chicken, pigs or cows. That is to say, our limited resources of feedstuffs will get more bang for the buck when fed to fish, shrimp or bivalves, than chickens, pigs and cows.

Back to aquaculture as a conservation tool.

As Waterlust founder, Patrick Rynne, discussed in a previous blog post, every product that humans produce has an environmental cost. The objective of an environmentally conscientious producer of anything is to make a product that satisfies the demand for it while creating the lowest ecological impact and staying within the carrying capacity of the environment.

Demand for seafood and protein is expected to climb dramatically over the next few decades. The global population continues to rise, large lower-income populations in China and India are increasing their GDP and adding more protein to their diet, and buying trends in North America and Europe are showing a shift from beef and pork towards chicken and seafood as people seek lower saturated fats in their proteins. Many environmentalists have pushed vegetarianism as a solution to reduce our ecological footprint and eating less meat is undoubtedly a very impactful way to lower your indirect carbon and freshwater consumption and should be encouraged. However, food is a powerful cultural and sociological cornerstone and large-scale dietary shifts do not occur in the timeframe needed to address our immediate marine environment concerns.

As a global strategy, not enough people are changing their eating habits to alleviate the need for lower impact protein production methods. We need alternatives that billions of people will get on board with and soon.

If there was ever a time to make a change in how we produce food, that time is now.In fact, change has been imposed upon us.Both protein producers and consumers all over the world have changed dramatically as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. There are large meat shortages in many countries as processing plants are forced to shutdown due to coronavirus cases. Seafood has seen similar issues although on a smaller scale but have also had to adjust their processes to account for the closing of restaurants where an estimated 70% of seafood is consumed in America. Seafood producers are turning to frozen or portioned and packed product forms to address this, but change doesn’t happen overnight.

Consumers are cooking at home at levels never seen before which leads naturally to a closer examination of one’s diet. Without intending to, I’ve been almost completely pescatarian during the quarantine (just a few pepperoni pizzas away from being able to make that claim without a qualifier) and have been eating vegetarian more often than not. Many of my friends are discovering the joys of bread baking, how quick and healthy oatmeal with berries can be and looking up the astounding nutritional profile of lentils and other pulses. How everything will shake out as businesses re-open is still very much uncertain, but there is no doubt that a shake-up is occurring.

Wild fisheries will continue to be an essential part of seafood production but should not be expected to fill the projected increase in demand. Wild capture fisheries are a finite resource so there are no more available fish to catch. We have maxed out most fisheries ability to replace themselves and, in many cases, should consider reducing catches to allow wild populations to recover.

Seafood is usually a more sustainable protein source than terrestrial protein. There are always exceptions to the rule such as wild-caught species that have high by-catch rates, but aquatic organisms have a few major advantages that make them very efficient to produce.

1) They are cold-blooded, so they don’t spend energy heating their bodies.

2) They don’t fight gravity.

3) They don’t spend energy building dense, heavy bones.

4) Swimming (or being a stationary filter feeder) is more efficient locomotion than walking or flying.

Aquatic organisms generally have better energy retention and protein retention capabilities than chicken, pigs or cows. That is to say, our limited resources of feedstuffs will get more bang for the buck when fed to fish, shrimp or bivalves, than chickens, pigs and cows.

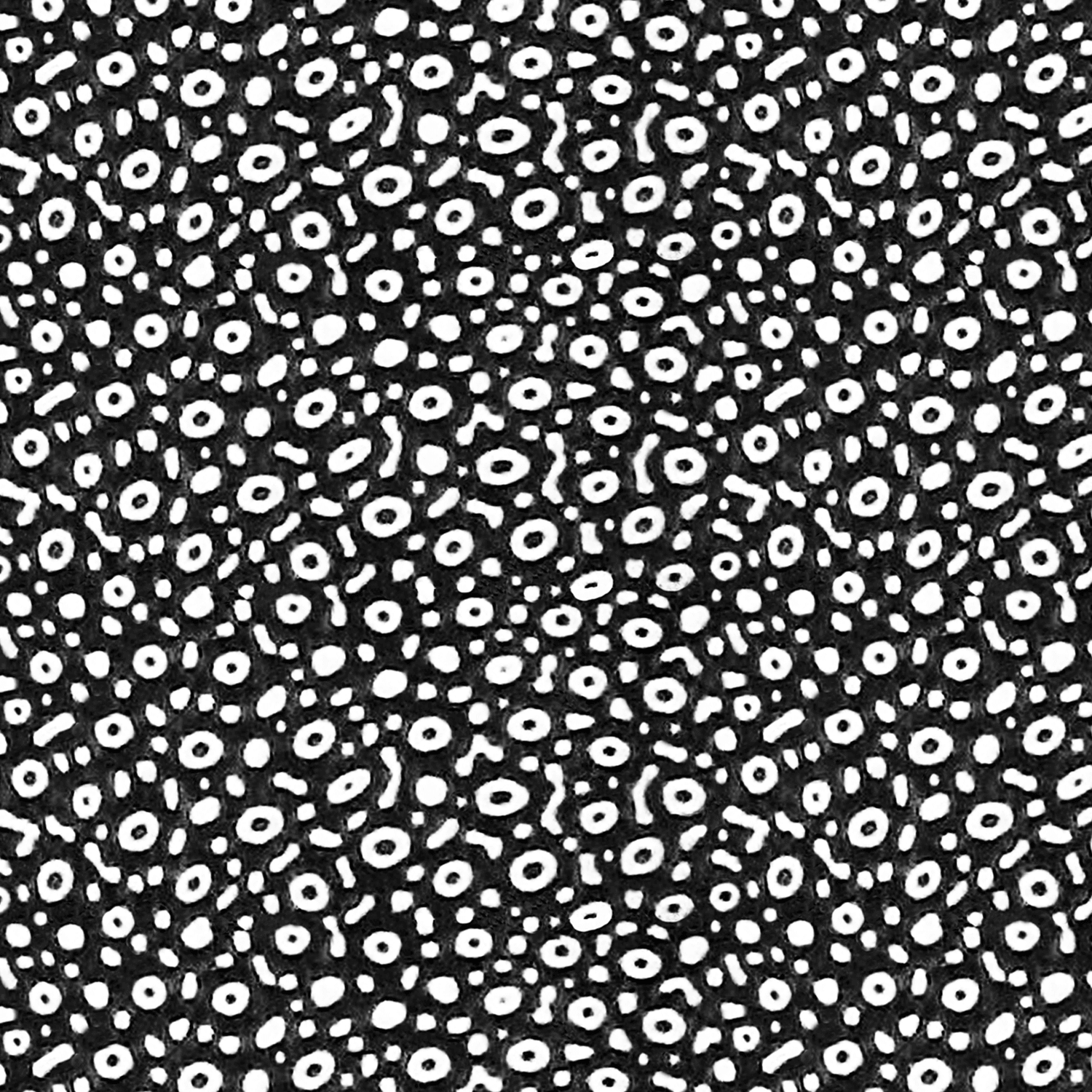

The whole process starts in a hatchery where these cobia eggs will incubate for 24 hours before hatching into larvae.

The environments that aquaculture farms utilize can be quite varied depending on the species and production method used. As the technology and interest in aquaculture gains traction, many farms, particularly those growing fish in the ocean, seek areas that have low background nutrients (they are oligotrophic), deep water with limited light reaching the bottom, stronger currents and low natural biodiversity. This has not always been the case but there has been a strong emphasis on finding more exposed sites over the past decade as a means to make fish farming easier. Knowledgeable farmers prefer these environmental conditions as lower productivity waters in the open ocean typically have higher oxygen levels, lower bacterial loads, lower parasites and less biofouling.

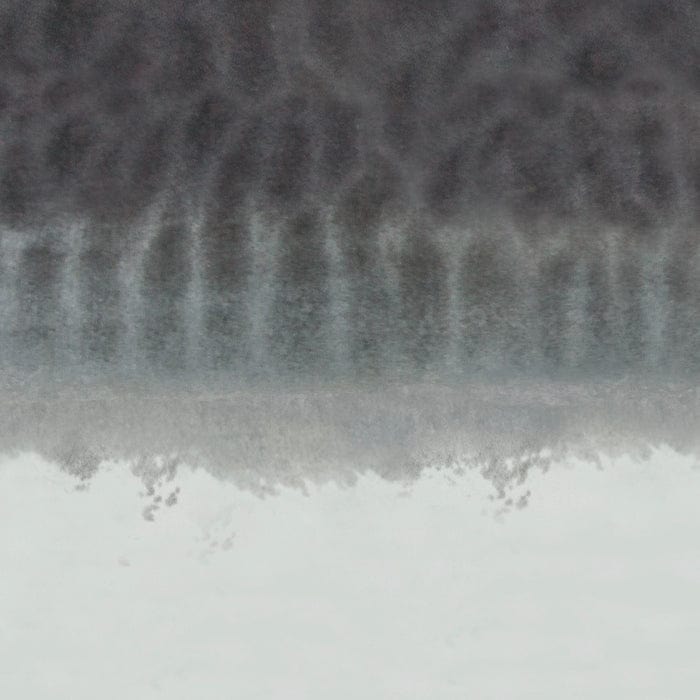

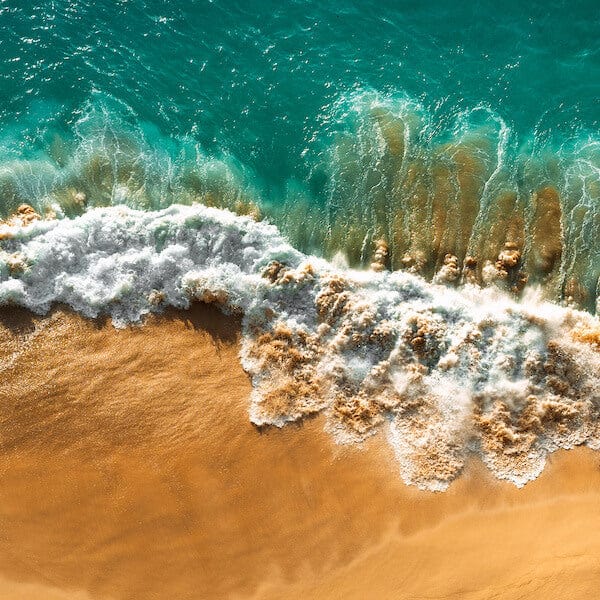

Regulators and conservationists also prefer having farms in these environments as it reduces conflict with other ocean users and these environments are much less sensitive than reefs, kelp forests or seagrass meadows and have a very high capacity to assimilate nutrients. Below is a photo taken during a benthic survey on a farm in Panama which shows the typical sandy or muddy bottom favored by many fish farms. I don’t mean to say these are ecological deserts, but environments like this are quite robust with the relatively few species present being generalists (they eat a wide variety of food items) and many of them are decomposers (they eat non-living organic material such as dead matter or waste products).

Many farm sites actually see an increase in both species richness and abundance after the installation of a farm since the farm operations act as a nutrient source within the carrying capacity of the ecosystem, and the farm equipment creates places for fish and shrimp to hide from predators and substrate for sessile organisms to grow on.

The environments that aquaculture farms utilize can be quite varied depending on the species and production method used. As the technology and interest in aquaculture gains traction, many farms, particularly those growing fish in the ocean, seek areas that have low background nutrients (they are oligotrophic), deep water with limited light reaching the bottom, stronger currents and low natural biodiversity. This has not always been the case but there has been a strong emphasis on finding more exposed sites over the past decade as a means to make fish farming easier. Knowledgeable farmers prefer these environmental conditions as lower productivity waters in the open ocean typically have higher oxygen levels, lower bacterial loads, lower parasites and less biofouling.

Regulators and conservationists also prefer having farms in these environments as it reduces conflict with other ocean users and these environments are much less sensitive than reefs, kelp forests or seagrass meadows and have a very high capacity to assimilate nutrients. Below is a photo taken during a benthic survey on a farm in Panama which shows the typical sandy or muddy bottom favored by many fish farms. I don’t mean to say these are ecological deserts, but environments like this are quite robust with the relatively few species present being generalists (they eat a wide variety of food items) and many of them are decomposers (they eat non-living organic material such as dead matter or waste products).

Many farm sites actually see an increase in both species richness and abundance after the installation of a farm since the farm operations act as a nutrient source within the carrying capacity of the ecosystem, and the farm equipment creates places for fish and shrimp to hide from predators and substrate for sessile organisms to grow on.

A screenshot from Tyler Sclodnick during an anchor inspection atOpen Blue Sea Farms, an aquaculture facility in Panama.

Developing aquaculture and adding capacity to produce seafood at a competitive cost and without depleting wild stocks allows farmed products to compete with wild-caught seafood in the marketplace. In the long term, this will reduce fishing pressure and lower the incentives for people to engage in illegal, unreported, unregulated fishing (often shortened to IUU fishing) without requiring any investment in coast guards, fisheries officers, protective policies, or marine protected areas. It is purely economic forces replacing protein products from overstretched wild fisheries or higher input-requiring terrestrial farms with products from an alternative industry.

And the markets have already spoken.

Aquaculture has been the fastest-growing food-producing sector in the world since 2010 and now produces more food for human consumption than wild fisheries.

Like any industry, there will be examples of irresponsible operators. Farms that stock their pens with too many fish or locate their farms in environments that cannot support them can create issues. But these are problems that can be dealt with through proper governance and regulation. Countries with strong aquaculture industries like Norway, Scotland and Canada have rigorous permitting and inspection programs that are very effective at protecting their environments and ensuring that farmed seafood products are safe and sustainable. And like any novel industry, the need for further advancements in feed compositions, pens and moorings technology, monitoring equipment, and other areas are still significant. However, these advancements will only be further delayed if the industry continues to be misunderstood.

So, don’t turn your nose up at farmed seafood.In a world with 8 billion people and counting, aquaculture will only become more prevalent and that’s a good thing.

Developing aquaculture and adding capacity to produce seafood at a competitive cost and without depleting wild stocks allows farmed products to compete with wild-caught seafood in the marketplace. In the long term, this will reduce fishing pressure and lower the incentives for people to engage in illegal, unreported, unregulated fishing (often shortened to IUU fishing) without requiring any investment in coast guards, fisheries officers, protective policies, or marine protected areas. It is purely economic forces replacing protein products from overstretched wild fisheries or higher input-requiring terrestrial farms with products from an alternative industry.

And the markets have already spoken.

Aquaculture has been the fastest-growing food-producing sector in the world since 2010 and now produces more food for human consumption than wild fisheries.

Like any industry, there will be examples of irresponsible operators. Farms that stock their pens with too many fish or locate their farms in environments that cannot support them can create issues. But these are problems that can be dealt with through proper governance and regulation. Countries with strong aquaculture industries like Norway, Scotland and Canada have rigorous permitting and inspection programs that are very effective at protecting their environments and ensuring that farmed seafood products are safe and sustainable. And like any novel industry, the need for further advancements in feed compositions, pens and moorings technology, monitoring equipment, and other areas are still significant. However, these advancements will only be further delayed if the industry continues to be misunderstood.

So, don’t turn your nose up at farmed seafood.In a world with 8 billion people and counting, aquaculture will only become more prevalent and that’s a good thing.

Tyler Sclodnick is the senior scientist for Innovasea, a company that is revolutionizing aquaculture and advancing the science of fish tracking to make our oceans and freshwater ecosystems sustainable for future generations. His work focuses on the development of sustainable fish farming technology and optimizing the site selection process.

Birgit Neil

May 25, 2021

Thanks, Birgit Neil for waterlust.com