It’s the middle of February and chilly for Bimini: Windy, cloudy and under 70 degrees, but the Bimini Biological Field Station’s (BBFS) band of sun-kissed scientists are undeterred.

“Since the weather isn’t going to be great tomorrow, we have a surprise for you,” our Bimini Shark Lab sherpa, Sophia Emmons quips, full of the sunshine that’s missing from the sky.

We’re now sitting in the periwinkle-walled belly of the Shark Lab, an approximately 3,000 square foot, bright blue facility crouched on a small canal in South Bimini. Since leaving Fort Lauderdale International Airport earlier that morning, our group of eight visitors – myself and my husband, a family of four and two singles – has already experienced our first shark encounter of the week.

The Bimini Biological Field Station on South Bimini Island, Bahamas

Most of us visiting the Shark Lab during this trip are not professional scientists or certified conservationists. We’re just regular people wanting to learn more about the ocean, specifically the sharks calling it home. This is one of the few times each year the BBFS opens its doors to people like you and I to join in “Field Expeditions.” I am fascinated by, yet fearful of, sharks. So in an effort to hedge fear through understanding I find myself a participant.

A highlight of this particular Field Expedition will be the opportunity to catch a close-up glimpse of Great Hammerheads. The migratory patterns of these critically endangered elasmobranchs makes Bimini one of the few places in the World where seeing them in the wild is possible with relative predictability.

Shark appreciation, though, isn’t just in the elusive.

“Anyone who doesn’t think sharks are cute, hasn’t seen a baby Lemon shark,” Emmons shares as she sets-up in the calf-deep water of a mangrove-lined spot near Bonefish Hole. While we wait for the baby Lemons to show, Emmons shares a little about her PhD research topic, which is one of the reasons she’s come to the Shark Lab.

Standing in a line as juvenile lemon sharks swim by

Day One: Lemon Sharks near Bonefish Hole

Rays scoot atop the seaweed blotched white sand as we casually explore the shallow area of Bonefish Hole. One of our group finds, and photographs, a strange looking creature that none of us recognizes. It’s later identified as a sea hare.

A bit later, we stand in a halfmoon surrounding Emmons and her bucket of fish bits. A light brown baby Lemon Shark cuts in through the seagrass, grabs a snack and shoots back into the shadows. Then another shows. Three Lemon sharks – about two to three feet in length – come closer and closer. Skittish at first, then eventually comfortable enough to pass between our legs.

Back at the lab, we gather around a large table painted with a beautiful map of the Bimini Islands. Between our escapades into the nearby waters, the Shark Lab hosts lectures in this room. Remote location on a non-profit budget require a unique resourcefulness evident at a glance. Things are everywhere, meticulously organized, stacked and labeled along handmade shelves. A line of yellow logbooks sit in striking contrast against the periwinkle wall. Milk crates are full of rope in varied thickness. There is a series of clear bins with intriguing classifications, like “Full DNA RADs” written on the outside. What looks like an old peanut butter jar is labeled “batteries.” Repurposed coffee tubs indicate they hold rubber bands.

Herman the Hammerhead!

During the first lecture, Emmons lifts Herman the Hammerhead, a 5.5 foot replica mount, from his perch on the wall and places him on the table. Over the next hour and a half Herman helps Emmons demonstrate how sharks are tagged, then tracked using different methods. When the presentation is finished, Emmons reveals tomorrow’s surprise. There has been a change to our itinerary due to inclement weather:

“We’re going to cage dive with bull sharks,” she says with a cheerfulness typically reserved for telling a child they are getting a puppy.

Then we’re off to dinner, which like every meal over the next five days, is homemade by the lab’s small team of ten, consisting mostly of graduate & PhD student volunteers. During the meal, our group gets to know one another with soft chit chat

Group Photo!

Day Two: Bull Shark Cage on North Bimini at the Bimini Big Game Club

Like predicted, the weather on our second day is overcast and very windy. The temperature is in the 60s -- cold by my Floridian standards. From the Pineapple House, where several of us are staying, the Shark Lab is a short, five-minute ride down one of the island’s dirt roads (the only paved road on South Bimini runs from the airport to the Ferry Dock).

After a quick breakfast gathered around long fold out tables, we collect our gear and head to the dock for a ferry connection from South Bimini to the North Island. We arrive at the Bimini Big Game Club Marina, which sits inside a bay formed by the belly of the hook-shaped Northern Island, unload our gear and wait for instructions.

As I fight into my wetsuit, I’m unsure whether I’m shaking from nerves, the cold or a combination. I’m thankful for a distraction. Emmons and her fellow Shark Lab colleague, Baylie Fadool, take us on a boat ride along the North Sound, a more developed area of the island.

When we loop along the shore, backhoes and dump trucks appear from behind mountainous man-made cliffs of sand: A strip of developable land, which will later support million-dollar homes atop a foundation created by dredging nearby waters. Matt Smukall, the BBFS President, assures it’s not a “good-guy bad-guy” thing.

“Our goal as fisheries managers is not to just shut everything [development and commercial fishing] down. It’s finding that balance of where we can do things sustainably,” he said.

Back at the Bimini Big Game Club, the cage isn’t like what I’ve seen on Shark Week episodes, dangling off a boat somewhere in the middle of the ocean. It’s attached to a dock in the resort’s marina. As others take their turn in the cage, those of us who wait are able to watch from above as the large sharks circle and snack. At the end of the dock, just above a ladder that descends into the cage, a woman sits monitoring tanks and time.

The dive cage at the end of the dock with sharks circling about.

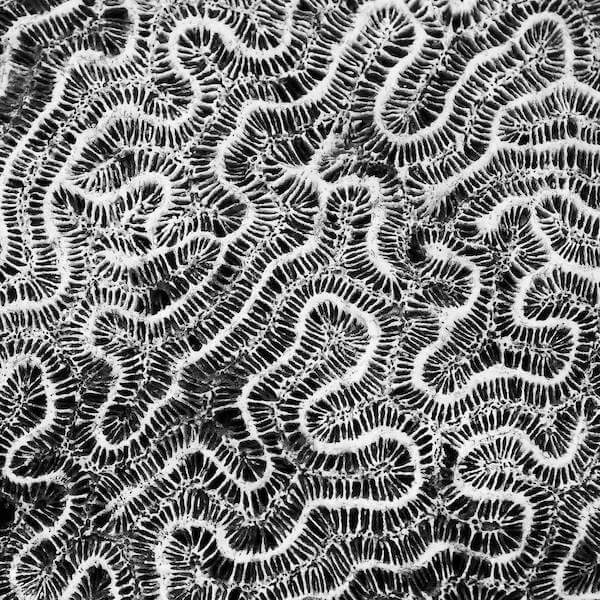

It is our turn. We’re reminded to keep our hands inside the cage at all times, then my husband descends. I follow. As I submerge my head underwater, the Darth Vader breathing of the regulator echoes. I can hear my breath quicken as I take in the surroundings. We are wearing weighted belts, but I struggle to steady as the cage rocks with the current and the movement of the seven Bull sharks circling outside. The irises of their mercury eyes are visible as they pass by, some close and quick, others slow and stealthy. Their movement is intoxicating, gunflint skin, white under bellies, some accessorized with remoras flowing like bicycle handlebar streamers. A few bump into one another, as if in a sharky game of Twister, uninterested in us or the cage. Some curiously float directly toward the cage and then suddenly whip upward, revealing partially open mouths, almost flicking notched caudal fins between the barnacled bars.

Just as I think I’ve got it figured out -- my heart rate and breathing seem to have leveled -- our time is up. A knock on the metal ladder from above lets us know it’s someone else’s turn, but I wanted to stay.

Our view from the cage, there were many sharks swimming closely by!

Days Three & Four: Searching for Hammerheads

Look to the left and the water darkens at the edge of the Gulf Stream. To right, the white bottomed ocean creates a turquoise ombre effect toward the South Bimini shore. The 20ft center console rolls lightly with the current as the group waits. Behind our idle chit-chat, a question rests at the tip of everyone’s tongue: Will any of the Great Hammerheads show up today?

During our day three and four excursions, the Great Hammerheads have not shown in their usual spots, so we venture out to see three other species: Caribbean Reef, Black Tip and Black Nosed sharks.

A 20-minute boat ride and the Shark Lab team has us anchored in a new location. None of us are scuba divers. We don’t need to be. A mask, snorkel and fins (and a wet suit for warmth) are all that’s needed. We cling to a buoyed rope that extends from our boat. Treading in approximately 25ft of water as the Caribbean Reef sharks roam below. They circle and weave, slowly almost in a single file line as if in a flight pattern. Their skin appears iridescent in the beams of sunlight that ripple in the current. I am again conscious of my quickened breath, but there’s no knee-jerk reaction to flee to the boat.

Another outing takes us to East Bimini where we encounter zippy Black Tips. Then we move on to a spot near Honeymoon Cay for a glimpse at juvenile Black Nose sharks and the chance to feed friendly rays and Nurse sharks.

Our group snorkeling off the coast of Bimini

Day Five: Elusive Elasmobranchs

We are back on the 20ft center console in the same spot we’ve waited twice before. Other boats gather nearby and wait. It’s the last day of our trip and we’re all hopeful that the Hammerheads will show today. For those of us not on the Shark Lab team, it’s our last chance to get a glimpse of these flatheaded, elusive ocean wonders.

During the past few days, tinges of concern permeate insights shared by Emmons and the other Shark Lab experts as they talk about the Hammerheads. Most years, anywhere from 10-14 individual hammerheads are typically sighted during the three-month winter period. However, during the 2021-2022 Winter season, only three of the “regulars” had been spotted.

The Shark Lab team is unsure as to why. Maybe they chose to winter somewhere else? If so, why? Of course, there is worry that the worst has occurred. Are these endeared regulars (the Shark Lab team talks of them by name, Atlas, Gaia, Selene, Medusa, etc. and can identify them individually by sight) still alive?

The hypothesis most clung to for the Hammerheads’ tardiness is that maybe they missed migratory cues because the area’s cold snap occurred later than usual.

Still, there’s hope. So we enjoy the sunshine, chat and take opportunities to swim near the Bull and Nurse sharks passing by.

The majestic Great Hammerhead. Photo by Baylie Fadool Bimini Biological Field Station

Unfortunately, we did not see any Great Hammerheads during the trip. However, from meeting wild rays, Caribbean Reef Sharks and Bull Sharks, to a snorkel through the shipwrecked Sapona, there were so many other highlights it’s nearly impossible to be disappointed.

It was clear during our encounters that sharks are not the vicious antagonists Hollywood so often depicts. In fact, with the right knowledge of shark behavior and proper precautions, it was even “safe to swim with sharks safely,” as the Shark Lab team often quipped.

While the Bimini Shark Lab knows a lot about sharks (it has the world’s longest and most consistent data set on Lemons), there are still many questions the lab’s rotating crew of scientists are trying to answer: What will the long-term impact of a planned development on the islands be on the area’s marine life? Where are the “missing” hammerheads? Where does the species go to mate? Is it mostly female Hammerheads that return to Bimini each year?

Five days following shark scientists was exciting and informative. I came away with a greater appreciation for sharks as well as the people who study them. I’m less fearful and am more sympathetic to (species-specific and overarching) shark plights.

As we head out, we drive over the same road we used to enter the island after arriving from the airport. But now we know: This road stands where mangroves once provided refuge for baby Lemon sharks. It’s a reminder of why the Shark Lab exists.

In the 32+ years since Dr. Samuel Grubber established the Bimini Biological Field Station and its training programs, Shark Lab scientists have been working to create a balance between protective policy, sustainable fishing and development.

These efforts have resulted in conservation-policy wins like the announcement of the North Bimini Marine Reserve in 2009 and the 2011 establishment of the Bahamas Shark Sanctuary, among others.

I arrived back at home thoroughly exhausted, thankful for the opportunity to participate in such a unique experience while meeting amazing people. Although tired, I was already plotting a return trip to South Bimini. I hoped the Great Hammerheads were doing the same.

Jessica Fuchs is a freelance writer and digital marketer. An aspiring seaplane pilot working on her PPL, she is passionate about ocean conservation and volunteers for the Volusia County Turtle Patrol. Jessica resides in Florida where she enjoys the sun, and all things water-related, with her husband, stepdaughters and Australian Shepherd, Fenek.

Connect with Jessica at Linkedin.com/in/jessicagreene

Ragan Mills

April 13, 2023

A great read! I’m so glad you let your curiosity take you on such an amazing and educational trip.